This post was originally published on this site

As polls show Americans are increasingly willing to get vaccinated against COVID-19, but a new journal article says behavioral economics and consumer research can help inform vaccine-promotion efforts for people who remain hesitant.

“Vaccine promoters will have to be creative in marshaling their resources and broad-minded in considering tools for addressing this enormous challenge,” wrote authors Stacy Wood, a professor of marketing at NC State University, and Kevin Schulman, a professor of medicine at Stanford University, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

About 5.9 million people in the U.S. had received their first of two COVID-19 vaccine doses as of Thursday morning, according to the CDC, in a slower-than-expected rollout. Some 21.4 million doses had been distributed.

The Food and Drug Administration in December granted emergency-use authorization to vaccines from Pfizer PFE and its German partner, BioNTech BNTX, and Moderna MRNA. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have recommended that that states prioritize access for health-care workers and long-term-care facility residents while supply is limited.

Recent survey research by the de Beaumont Foundation and pollster Frank Luntz found that family is the best motivator to get people vaccinated against COVID-19. Asked who they would be most willing to take the vaccine for other than themselves, 53% of respondents said they would do it for their family — far outstripping options like their country/America (20%), the economy (13%), their community (8%), and their friends (6%).

It’s more effective to emphasize the benefits of vaccination rather than “moralizing and lecturing,” the poll also found.

Avoid moralizing

The national strategy to boost COVID-19 vaccine uptake should consider targeting messages based on people’s specific identity or social group-related barriers to getting the vaccine — for example, a blunt ‘Go out with a bang, but don’t die this death’ campaign for groups with a Covid-defiant identity,” they wrote.

Different messages are needed to reach some people of color whose hesitancy stems from mistrust of the medical establishment, or older Republicans who are “afraid to rock the boat.”

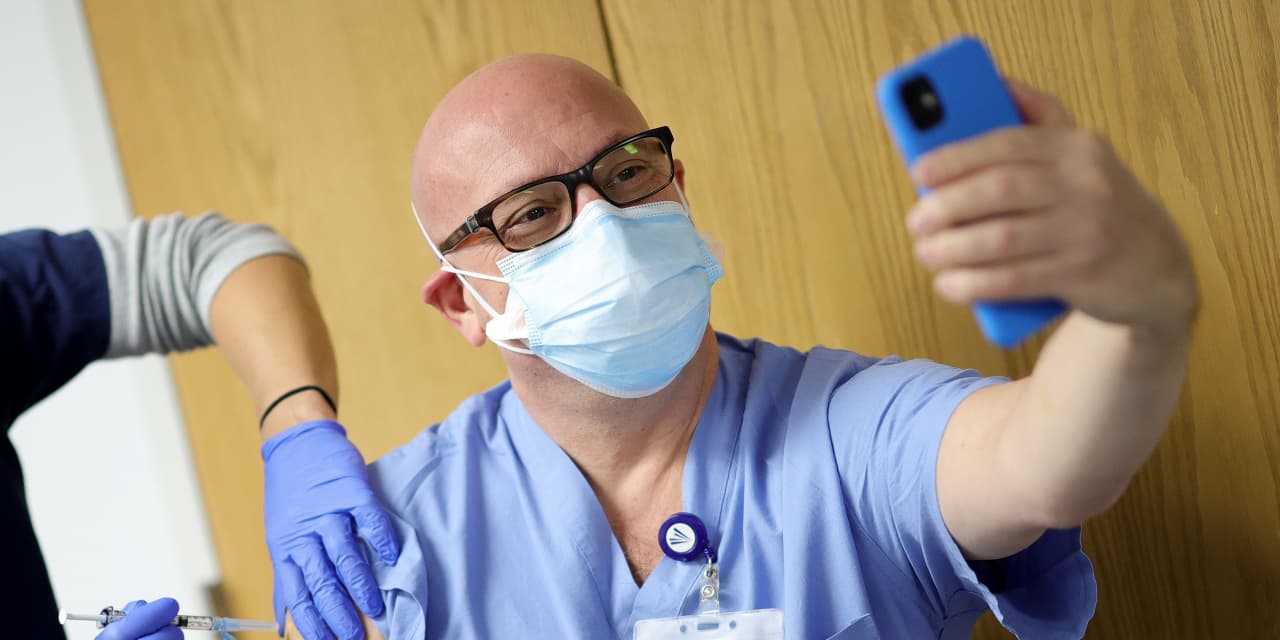

The authors, drawing a parallel to the launch of Apple’s AAPL, +0.86% iPod and its iconic white earbuds, also suggested that making it easy for consumers to “observe” that others had been vaccinated could help increase adoption. They suggested “wearable tokens” such as stickers, bracelets or pins, as well as “digital badges” on social media.

Analogies — like telling someone they’re more likely to get struck by lightning than die from COVID-19 after being vaccinated, or likening mRNA, the molecule used in both authorized vaccines, to “a teacher that shows the body how to make the antibodies that fight off Covid” — can help convey complex information in a familiar way, the paper said.

‘Fear of missing out’ or FOMO

The authors also raised the idea of treating vaccination “as a desirable opportunity not to be missed,” and creating rewards that inspire action based on FOMO (fear of missing out).

Employers could give employees the day off to get inoculated, insurance rebates and tax deductions could provide financial incentives, and colleges could hand out tickets to future events, they said.

Based on research about consumers’ tendency to seek “compromise options” like a medium-sized coffee, the authors suggested providing multiple vaccination options rather than a binary choice, and framing vaccination “as a middle or normal choice.” For example, vaccine promoters could “ask people if they will get the vaccine later, get it now, or get it now and sign up to donate plasma,” they said.

“ Identifying a common enemy can also help, the authors added, noting the obvious threat of the virus. Since some people in the country still don’t see the COVID-19 as a legitimate concern, public-health officials for now could focus on ‘downstream effects’ of the virus. ”

Other recommended strategies included leveraging the natural scarcity of vaccines by painting those who get them first “as nationally valued and honored.”

This includes anticipating and addressing “negative attributions,” such as people from disadvantaged neighborhoods potentially feeling like they’re being used as “lab rats” to test the vaccine; and reminding people of unlikely but high-stakes potential consequences of not getting vaccinated, like becoming a so-called long-hauler or losing a family member to the disease.

Identifying a common enemy can also help, the authors added, noting the obvious threat of the virus. Since some people in a polarized U.S. still don’t see the COVID-19 as a legitimate concern, public-health officials for now could focus on “downstream effects” of the virus: “We can focus on ‘battling’ poverty by getting people back to work or on ‘racing’ other countries to return to normal,” they wrote.

Different strategies might be more applicable for different health entities, Wood and Schulman wrote. “Given [the] level of investment, skill, and good fortune in developing a vaccine, it will be tragic if we fail to curtail the virus because Americans refuse to be vaccinated,” they added.

While experts say it’s still difficult to cite a definitive estimate for what percentage of the U.S. would need to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity against COVID-19, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Anthony Fauci has suggested the number could be between 75% and 85%.

About 62% of respondents said the statement “getting vaccinated will help keep you, your family, your community, the economy and your country healthy and safe” was the most convincing message to get vaccinated. Only 38% said the same of the statement “taking the vaccine is the right thing to do” for those entities.