This post was originally published on this site

In this exceptional year, much of our collective attention span was spent on the pandemic, the U.S. election, geopolitical tensions, and social media paroxysms. When it came to US-China in particular, there simply wasn’t enough “China” as the bilateral dynamic was regularly filtered through the prism of the pandemic and the U.S. election.

Focusing on the daily rigamarole obscured subtler, and ultimately more consequential, developments. Stepping back at the end of 2020, we want to highlight two overlooked and two overhyped trends that, in our judgment, will matter greatly to China’s political economy and for how it adjusts to a dramatically changed external environment.

Overlooked

1. Closing the curtain on the GDP-obsession era

The signs have been there, but it wasn’t until 2020 that the writing clearly appeared on the wall: GDP growth will no longer hold sway over China’s development.

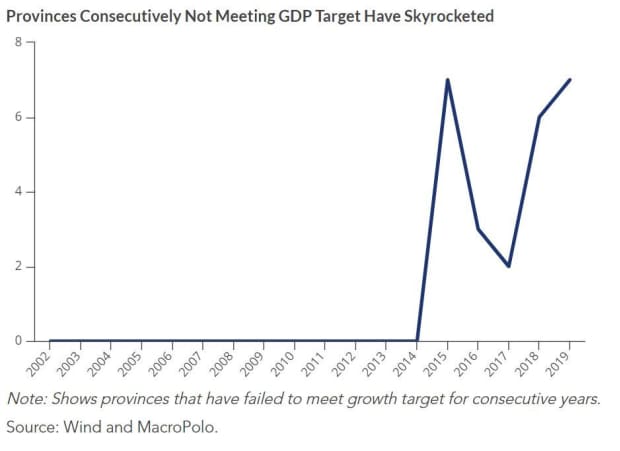

The number of provinces that have repeatedly failed to meet national growth targets has already surged, with no apparent political consequences. Xi Jinping had also signaled in April 2020 that Beijing is willing to accept regional growth divergences. That likely foreshadowed what was to come in the 14th Five-Year Plan in November 2020, which was accompanied by Xi’s unprecedented explanation of why it didn’t include a specific growth target.

Although some observers have noted this shift on GDP, its significance may be underappreciated. It is tantamount to simultaneously reshaping political incentives, changing the investment-driven model, and redirecting focus toward de-risking and reforming the economy.

In short, the Xi administration has been unexpectedly tolerant of austerity—a precondition for ramming through very difficult structural reforms that are essentially growth-negative in the near term.

2. Decoupling is everywhere except in reality

If a single word were chosen to define U.S.-China in 2020, “decoupling” would be a good candidate. Bandied about with abandon, the term has created the perception that these highly complex supplier networks were being severed in real time. What has been overlooked is just how little meaningful decoupling actually happened.

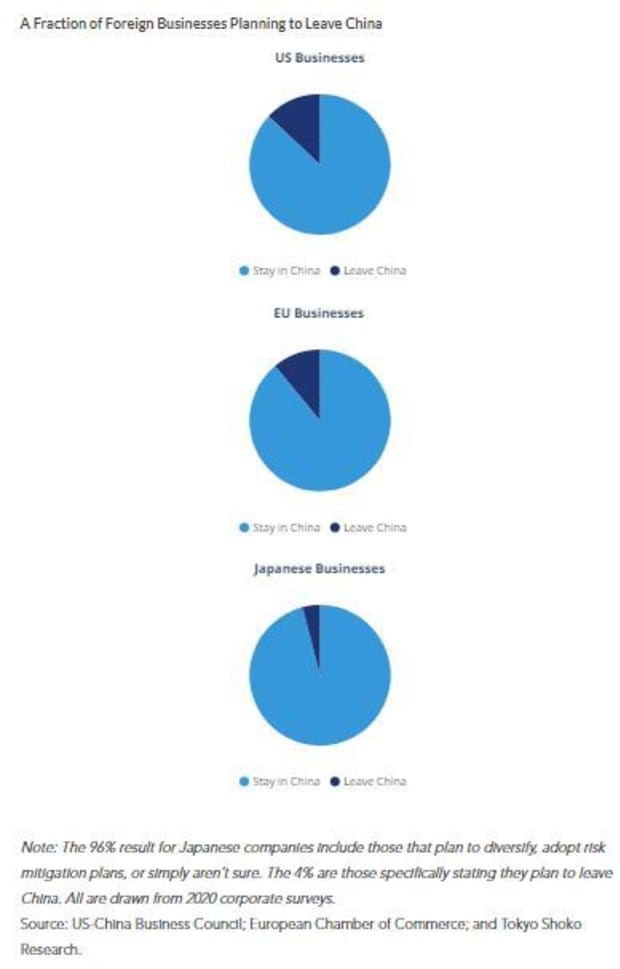

Foreign businesses are just one gauge of decoupling, but they are particularly important leading indicators of shifts in supply chain ecosystems. In 2020, the respective portions of U.S. (87%) and European (89%) businesses indicating no intention to leave China are as high or even higher than they’ve been in recent years. And despite the Japanese government creating a fund to help re-shore its manufacturers, only 4% of Japanese businesses said they’re definitively leaving China.

Pandemic disruptions certainly weighed heavily on firms’ decisions, likely delaying drastic changes or planned investment. It is also true that many companies want to diversify beyond China—some already have—to hedge against risk. Nonetheless, what has actually happened on the decoupling front appears disproportionately modest relative to the attention heaped on it.

Overhyped

1. China slams the door on the world

Whether it is “Made in China 2025” or “social credit,” any official neologism emanating from Beijing now gets spotlighted, scrutinized, and sometimes hyped. The latest offering of “dual circulation” is no exception, with many interpreting it as China’s pivot toward withdrawal from the world.

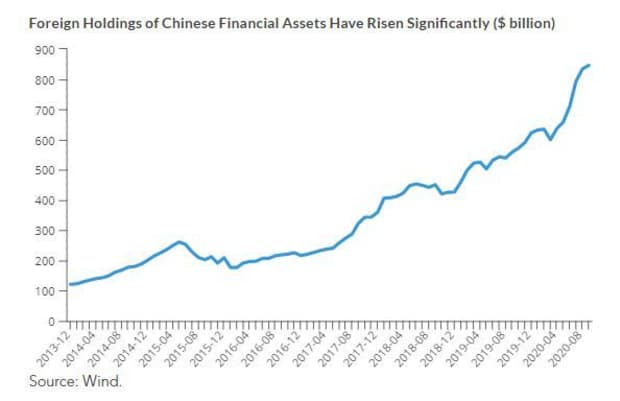

Yet when it comes to capital markets, China has gone in precisely the opposite direction, further linking itself to global capital. Although market openings began around 2018 and capital inflows rose steadily since, it wasn’t until 2020 that foreign capital inflows saw a notable spike. Moreover, the inking of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) trade deal and the potential conclusionof an EU-China investment treaty hardly suggest a Beijing that is closing its doors on the world.

To be sure, technology is an area in which China does want to reduce dependence on imports. But even there it would be unrealistic to assume that China will achieve anything close to total indigenization.

2. BRI is down but not out

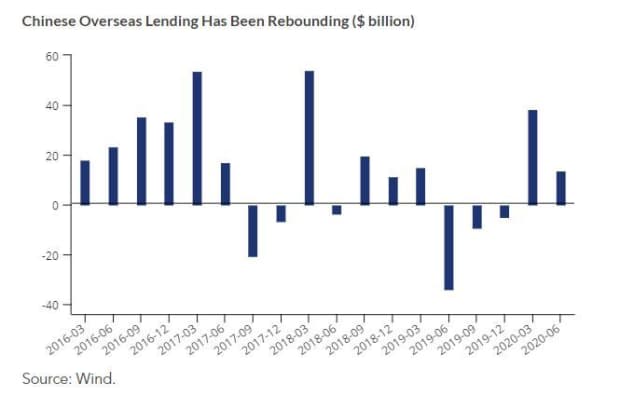

China’s overseas lending plummeted in 2019, leading some to prognosticate the death knell of the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI). Yet China’s overseas lending has risen in 2020, though it has not returned to the heights seen in 2017 and 2018.

This makes sense as fierce internal debate and external pressure likely pushed Beijing to make necessary adjustments and curtail some of its ambitions for the BRI project. But gone it is not, since Beijing rarely throws out the baby with the bathwater, particularly for a signature initiative that has Xi’s imprimatur.

The 2019 lending collapse can be partly explained by the political upheaval at the China Development Bank (CDB), a major financier of BRI projects, when its former president was arrested on corruption charges. As a result, the CDB’s total assets only increased by 2% in 2019. But the policy bank is actively lending again, having recently committed more than $80 billion to projects under RCEP, some of which can surely be rebranded as BRI projects.

Damien Ma is director of MacroPolo, the think tank of the Paulson Institute in Chicago. Houze Song is a research fellow at MacroPolo. This was first published by MacroPolo — “Rethinking 2020: What’s Overlooked and What’s Overhyped“.