This post was originally published on this site

A growing share of Americans (45%) say they plan to get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it’s available or a few weeks after, according to a new Axios-Ipsos survey conducted Dec. 18 to Dec. 21 — up from 38% a week earlier and 29% in September.

In a separate USA Today/Suffolk University poll conducted Dec. 16 to Dec. 20, 46% said they would take the vaccine as soon as they can, a leap from the 26% who said so in late October. And a Pew Research Center poll conducted in November found 60% of U.S. adults said they would get a vaccine if it were “available today,” up from 51% two months earlier.

This snapshot of public sentiment, captured as vaccine makers roll out initial doses, bodes well for vaccine uptake as the pandemic continues to claim American lives and livelihoods.

After all, epidemiology is a numbers game — and “the more cases there are, the more cases there will be, period,” said Emily Landon, the executive medical director of infection prevention and control at University of Chicago Medicine.

“The more people who get vaccinated [against] COVID, the more people who will be immune to COVID. The more people who are immune to COVID, the less likely it is that you’ll have close contact with someone who has COVID,” Landon told MarketWatch. “And if you’re the one who gets vaccinated? Even better.”

Vaccination offers two benefits, said Joshua Epstein, a professor of epidemiology at the NYU School of Global Public Health: direct protection of the person vaccinated, as well as the social benefit of vaccinated people not spreading the disease to others.

“If enough get vaccinated, the disease can die out on its own for lack of fuel,” Epstein said. “That’s the herd-immunity idea: Protect enough people that it has insufficient fuel to keep burning.” The goal of a vaccination strategy, he added, “is to tip the epidemic into that declining state.”

How many people need to get vaccinated

The vaccine candidate from Pfizer PFE, -0.45% and its German partner, BioNTech BNTX, -3.10%, showed 95% efficacy in protecting against COVID-19 in a late-stage clinical trial. Moderna’s MRNA, -5.33% vaccine showed about 94% efficacy.

It remains unclear whether the two vaccines, which received emergency-use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration this month, protect against symptomless COVID-19 infection or transmission. Preliminary data from Moderna’s trial suggested there may be a lower risk of asymptomatic infection after one dose, though further analysis is needed.

“ Estimates vary on what share of the population would need to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in order to achieve herd immunity, and experts warn that it’s hard to pin down a definitive figure just yet. ”

Both consist of two doses: Pfizer’s requires a second shot three weeks after the first, while the Moderna shots come four weeks apart.

At least 614,117 U.S. vaccine doses had been administered as of Monday morning, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; that tally only included Pfizer doses. Some 4.6 million doses of both vaccines had been distributed.

The U.S. has never reached herd immunity from natural infection with a novel virus; so far, vaccination has always been required. Estimates vary on what share of the population would need to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in order to achieve herd immunity, and experts warn that it’s hard to pin down a definitive figure just yet.

See also: Doctors and scientists take aim at herd immunity, calling it ‘nonsense’ and a ‘nebulous’ idea

Moncef Slaoui, the Trump administration’s vaccine czar, told CNN in November that with the roughly 95% efficacy level demonstrated by Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines, “70% or so of the population being immunized would allow for true herd immunity to take place.” “That is likely to happen somewhere in the month of May, or something like that, based on our plans,” he said.

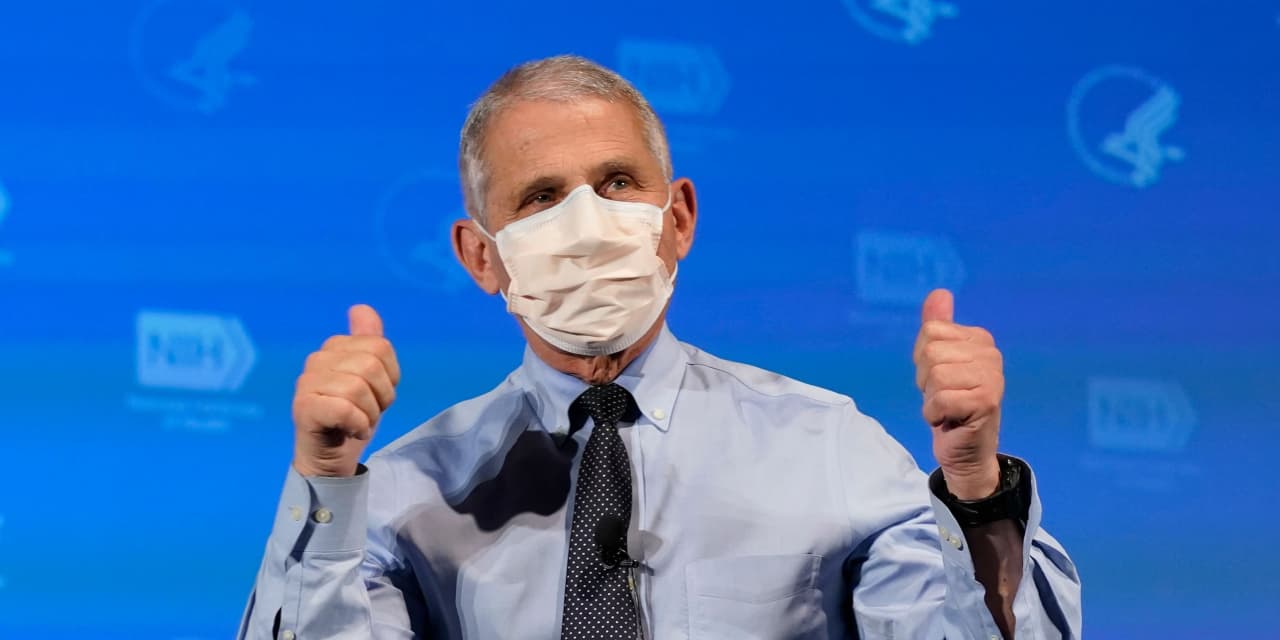

Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious-disease doctor, said during a Nov. 30 livestream with Facebook FB, -0.26% CEO Mark Zuckerberg that while he wasn’t yet sure what percentage of the population would need to get vaccinated against COVID-19 to achieve herd immunity, “I would imagine it’s somewhere between 75 and 85% at least.”

“If you have a highly efficacious vaccine and only 50% of the country gets vaccinated, you’re not going to have that umbrella of protection of herd immunity,” Fauci added. “What you really want is one, what we have, a highly efficacious vaccine — but you want 75, 85% of the people to get vaccinated.”

The percentage of people that will need to be vaccinated will depend on the actual vaccine efficacy in real life and any future vaccine efficacy, Landon added.

“If everyone got one of the mRNA vaccines and they worked about 90% of the time, we would need to vaccinate about 10% more than the ‘herd immunity’ target, whatever that may be,” she said. (mRNA technology, employed in both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, teach the body’s cells to create proteins that generate an immune response.)

“ As for concern over a new COVID-19 strain identified in the U.K., public-health authorities caution against overreaction and say there is no evidence it would render current vaccines less effective. ”

Why? Because some people who get vaccinated will not actually be protected, Landon said — something that’s true of any vaccine.

“When a vaccine is 95% effective, that means 95% of the people are protected. In some populations that number is lower (older individuals, probably immunocompromised), and higher in others (young healthy people). There are more old and immunocompromised people in real life than the trial, so I estimated about 90% overall,” she said. “So in order to average 70% of people immune, you’ll have to vaccinate more than 70% (probably 75 to 80%).”

As for concern over a new COVID-19 strain identified in the U.K., public-health authorities caution against overreaction and say there is no evidence it would render current vaccines less effective. Much remains unknown, and the CDC has not identified the strain in the U.S. But if it turns out to be more easily transmissible than other strains of the virus, as some early reports have predicted, a higher level of vaccine coverage might be necessary to produce herd immunity, Epstein said.

“If the virus becomes more efficient in infecting people, we might need even a higher vaccination rate to ensure that normal life can continue without interruption,” BioNTech CEO Ugur Sahin told the Wall Street Journal this week. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is highly likely to work against this variant, he added.

One way to promote vaccine enthusiasm

There’s still plenty of work to be done to encourage vaccine uptake among groups that may be hesitant, including some people of color whose mistrust of the government and health-care system stems from a history of medical racism and experimentation, said Lindsey Leininger, a public-health educator on faculty at Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business and “Nerdy-Girl-in-Chief” for the science-communication project Dear Pandemic.

“ A recent study found that ’emphasizing the benefits of being a protector for others (instead of yourself) looks to be more effective in promoting greater adherence to recommended practices.’ ”

But one evidence-based approach seems promising for the overall vaccine outreach and education effort: promoting the idea of being a “protector.” Research suggests that communicating about herd immunity and the protection vaccination offers — not just to oneself, but to others — can boost intention to get vaccinated, Leininger said.

A recent study published in the journal Patient Education and Counseling found that “emphasizing the benefits of being a protector for others (instead of yourself) looks to be more effective in promoting greater adherence to recommended practices” regarding COVID-19 safety guidelines, according to its co-author, University of Michigan associate professor of general medicine Lawrence An.

“Coaching people and educating people around the indirect benefits they’re going to proffer once they get vaccinated is going to be really important,” Leininger said. “It’s going to help vaccine enthusiasm.”

After all, she said, everyone has someone close to them who’s vulnerable to a bad COVID-19 outcome, whether it’s a grandmother, a loved one with diabetes or an immunocompromised child. “The idea of protecting that person is the most powerful motivator for action around,” Leininger said, “and I think that that’s going to resonate and land for vaccination as well.”

‘You should jump to get that vaccine’

Once it’s your turn to get inoculated — which public-health experts project will be in the spring or summer, assuming you’re not in any high-priority group — “you should jump to get that vaccine,” Landon said.

“You want to get as many people out of the spreading dynamic as soon as you can, because epidemics have this exponential growth property,” Epstein added. “One can give it to several, and they can give it several and so on — so the earlier you can nip that process in the bud, the better off you are.”

In practical terms, the only way the U.S. will get to a point where masks and social distancing are no longer necessary and restaurants aren’t closed “is if everybody gets vaccinated,” Landon said. “And the faster we do it, the faster we get back to life.”