This post was originally published on this site

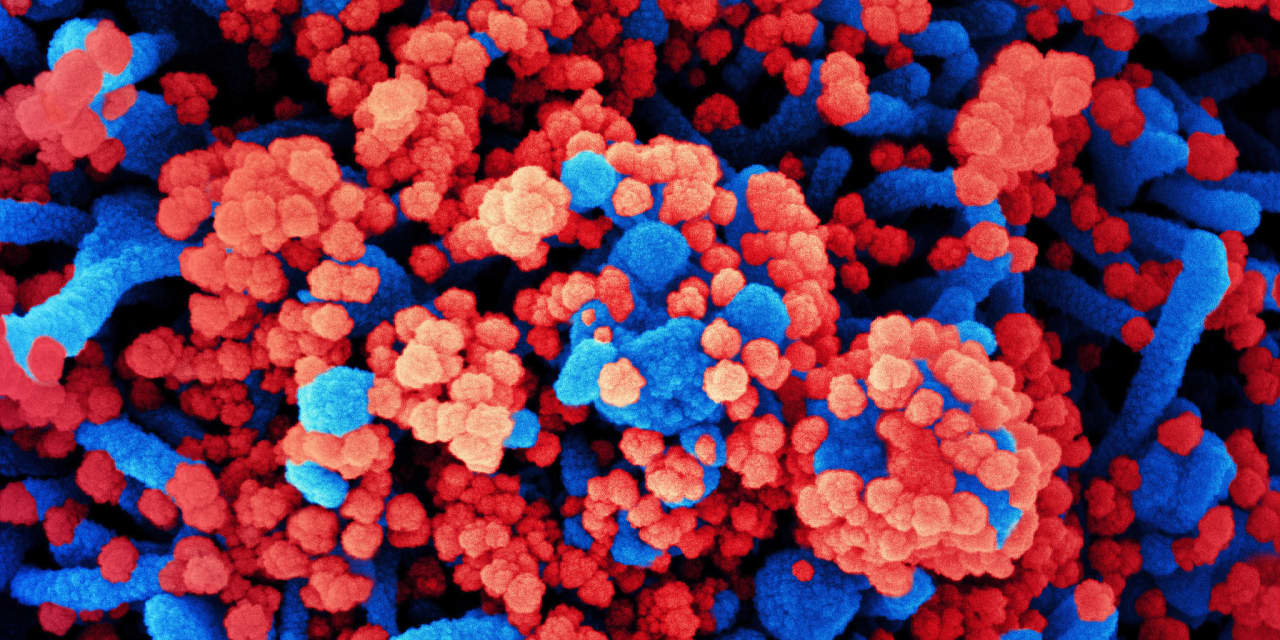

A new strain of COVID-19 identified by researchers in the United Kingdom has set off concern about the possibility of a more infectious variant of the coronavirus moving into the U.S. at a time when cases are at all-time highs.

What do we know so far?

U.K. health officials first notified the World Health Organization on Dec. 14 about the new variant, which has 14 mutations and is called VUI – 202012/01 or B.1.1.7. VUI stands for “variant under investigation.”

A preprint providing additional details about the variant was published the following day by University of Cambridge researchers. (A preprint is a type of early-stage medical study that has not yet been peer-reviewed. It has become a common way to disseminate scientific research during the pandemic.)

The strain was identified from about 250,000 sequenced genomes of people who had tested positive for COVID-19. The U.K. has sequenced between 5% and 10% of the nation’s roughly 2.1 million COVID-19 samples, according to the WHO. (The U.S., in comparison, has sequenced roughly 51,000 of the 17 million positive tests, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said it has not identified this variant.)

According to the preprint, the mutation was found in about 3,000, or 2.5%, of the 246,534 SARS-CoV-2 sequenced genomes housed in a central database, as of mid-December. As a result, “limitation of transmission takes on a renewed urgency,” the researchers wrote. The strain has become more prevalent since August, primarily in Denmark and the U.K., which had 1,108 cases, as of Dec. 11.

How have governments responded?

The confirmation of the new strain has set off concern among governments around the world.

U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson said Dec. 20 that the new strain “appears to spread more easily and may be up to 70% more transmissible than the earlier strain.” European Union countries and Canada have since closed their borders to the U.K., and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo called for the federal government to halt flights from the U.K. into the U.S. (At least three airlines, Virgin Atlantic, Delta Air Lines Inc. DAL, -2.99%, and British Airways, have now agreed to test passengers flying from the U.K. to New York.)

Why does this mutation strain matter so much?

The coronavirus, which China first told world health officials about Dec. 31, has mutated a number of times.

Most notably, researchers said back in May and June that there were two dominant strains then — the D614 virus that originated in Wuhan, China, and was likely brought to the West Coast by travelers at the start of the year, and a mutated strain that came to New York (and the rest of the U.S.) by way of Europe. That G614 virus is now considered the dominant strain in the U.S. It is also considered much more infectious than the D614 virus, though it is unclear why.

However, public health officials are cautioning against overreaction to the new variant, given the lack of unknowns about how it behaves and whether it is, in fact, more infectious.

Public Health England said this week that “the new variant transmits more easily than the previous one but there is no evidence that it is more likely to cause severe disease or mortality.” The CDC put out a similar statement, saying “there is not enough information at present to determine if this variant is associated with any change in severity of clinical disease, antibody response or vaccine efficacy.”

“This new variant has emerged at a time of the year when there has traditionally been increased family and social mixing,” the European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention said this week. “There is no indication at this point of increased infection severity associated with the new variant.”

Will the new variant affect the immune response triggered by COVID-19 vaccines?

We don’t know. The CDC and the WHO have said there isn’t enough information at this time to know if the strain can challenge the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines; however, the CDC cautioned that it could become a concern but it is not one right now.

“The ability to evade vaccine-induced immunity would likely be the most concerning because once a large proportion of the population is vaccinated, there will be immune pressure that could favor and accelerate emergence of such variants by selecting for ‘escape mutants,’” the CDC said. “There is no evidence that this is occurring.”

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, a foundation that is funding development of COVID-19 vaccines globally, said it hasn’t seen any indication at this time that vaccine effectiveness will be impacted but it plans to monitor how and if new strains affect vaccines. “We’ve seen nothing so far that suggests the virus can evade the recently developed vaccines,” a CEPI spokesperson said in email.

BioNTech SE BNTX, -5.54%, which developed a COVID-19 vaccine with Pfizer Inc. PFE, -1.71% that is now authorized in a handful of countries, is seeking to reassure the public that their vaccine remains an effective protective tool against the virus.

“If the virus becomes more efficient in infecting people, we might need even a higher vaccination rate to ensure that normal life can continue without interruption,” BioNTech CEO Ugur Sahin told The Wall Street Journal this week. He also said Tuesday during a news conference that “scientifically, it is highly likely that the immune response by this vaccine also can deal with the new virus variants.”

RBC Capital Markets’ Brian Abrahams told investors that even if a mutated form of the virus lowers the efficacy rates of vaccines, that “would only have a modest effect on the time to achievement of herd immunity.”

Shares in the three companies with COVID-19 vaccines authorized by the Food and Administration dropped in trading on Tuesday. Shares of Moderna Inc. MRNA, -8.98% were down 9.4%, while Pfizer’s stock fell 1.5% and BioNTech shares dropped 7.1%. The S&P 500 SPX, -0.21% was down 0.1%.