This post was originally published on this site

A friend of mine just made a ton of money in a tech company. He’s looking forward to financial independence and early retirement, probably in the next year or two.

And when that happens, he’ll want to live on passive income, that means he’ll want his investments to throw off enough cash each year so he can live on it.

Nice work—if you can get it. Here are seven points to consider.

1. Watch out for TIPS. Not long ago these were the perfect low-risk, sleep-at-night retirement investment. Treasury inflation-protected securities are Treasury bonds whose interest payments effectively adjust to compensate for rising inflation. At points in the past 20 years they’ve offered inflation plus 3% a year: A terrific return with effectively no risk. But not any more. Right now TIPS offer inflation minus. They are literally sporting negative “real,” inflation-adjusted yields, meaning anyone owning a TIPS fund is locking in a guaranteed loss of purchasing power if you hold the bonds to maturity.

2. Watch out for regular Treasury bonds too. The 10 year Treasury TMUBMUSD10Y, 0.923% sports a yield, or interest rate, of just 0.9%. The bond market, meanwhile, is predicting inflation of at least twice that over the next 10 years. Even the longest Treasury bond offers an interest rate of just 1.7% for 30 years—locked in. If we get inflation or higher interest rates ahead, or both, these bonds will become what they were called in the 1970s: “certificates of confiscation.” That’s as unpleasant as it sounds.

3. He’s looking at becoming a landlord. He’s already bought one property. This is a popular strategy among those seeking passive income. I can only say: Better you than me. Get a bad tenant and you can be locked into a financial and legal nightmare, as friends of mine have found. And real estate can be hard and costly to sell—indeed in a crisis there is often no market at all. Individual properties can entail plenty of risk. I don’t understand why these people don’t look at publicly traded real estate, namely REITs, instead. There are bargains aplenty at the moment, here and (especially) internationally. According to FactSet, US REITs are currently yielding 3.8% on average and non-US REITs 4.8%. Critically, REIT dividends, unlike bond coupons, typically rise over time. The simple Vanguard Real Estate Index Fund VNQ, -0.68% and Vanguard Global ex-U. S. Real Estate VNQI, -0.95% are diversified and low fee (and held in retirement accounts by members of my family). The iShares Global REIT ETF REET, -1.00%, also with low fees, is about two thirds U.S., one third foreign.

4. Look at infrastructure stocks, says Joachim Klement, strategist at London-based investment bank Liberum and a trustee of the CFA Institute’s Research Foundation. While good yields are scarce across all assets, he says, “we think that infrastructure stocks (as opposed to direct infrastructure investments) are currently the best option for passive income.” Infrastructure, he says, “is more than utilities. It also includes toll roads, airports, railways etc., which are often part of the industrials and transport sectors.” He adds: “Institutional investors have invested heavily in direct infrastructure investments, driving valuations to unprecedented highs. Meanwhile listed infrastructure companies like gas and water utilities or operators of toll roads and bridges have been overlooked.” The SPDR S&P Global Infrastructure ETF GII, -0.58%, although it has a hefty 0.4% annual fee, is a one-click global option here and currently yields 3.34%. Like REITs, the dividends typically rise over time.

5. Don’t overlook stocks for income. FactSet’s broad index of U.S. stocks has a dividend yield now of just 1.5%, though this is a bit misleading because U.S. companies spend “dividends” buying in stock as well. Overall, corporate dividends have been less volatile than the history of the stock market would suggest. Yes, they can go down: They did in 2008-2011, due to the financial crisis, and they plunged in the Great Depression. But that varies a lot by industry. Financials saw the biggest collapse during the last crisis, for example. Consumer “non-durables”—companies that sell toilet paper, dishwashing liquid, and so on—pretty much sail through.

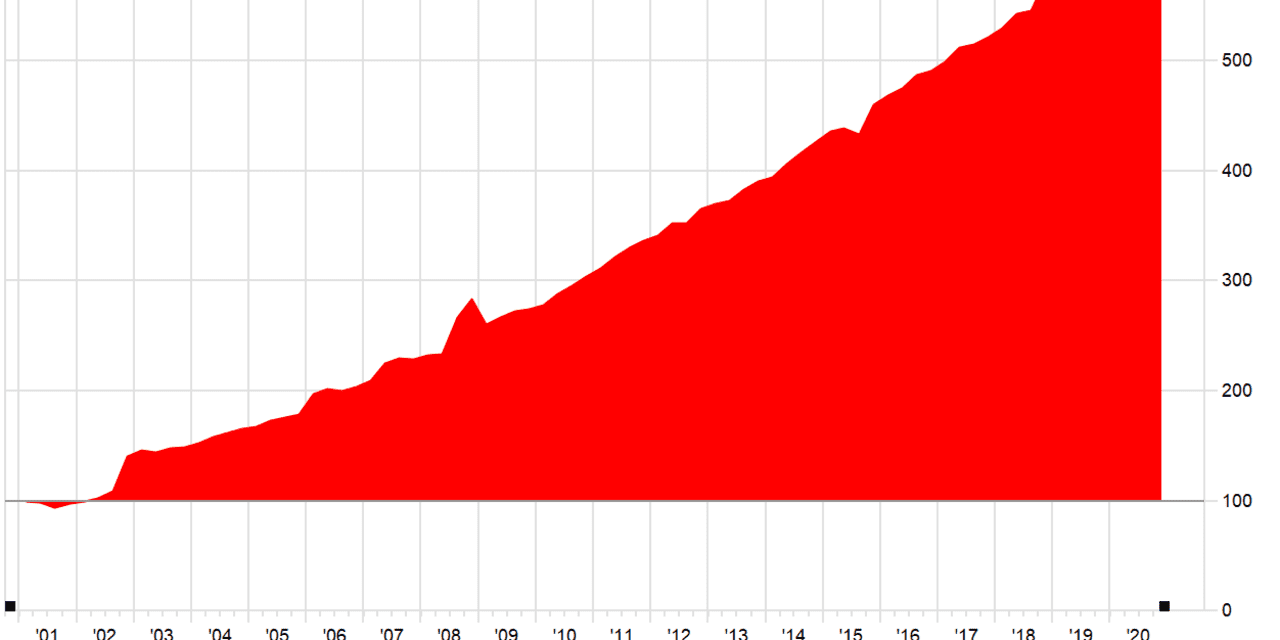

6. Selling options. This is less crazy than it sounds, though it merits a detailed discussion of its own. If you own regular stocks, and then sell options on the stock, in essence what you are doing is giving up some of the volatility, and potential for huge gains, in return for steadier returns. The Cboe BuyWrite Index, which tracks a mainstream version of this strategy, has generated average returns of 4.23% a year for 20 years. The opportunistic Glenmede Secured Options mutual fund GTSOX, +0.16% has returned 9% a year, on average, over the past 10 years. (That’s net of fees, which are 0.87% a year). And the outlook ought to be above average: Portfolio manager Stacey Gilbert says option prices are still elevated due to the crisis. But she warns the strategy involves stock volatility risk. “Under no shape or form should someone assume a covered-call strategy is a zero beta to stock strategy,” she says.

7. Lifetime annuities are riskier than they look. Arguably the safest way to generate income in retirement is to convert your wealth into an immediate annuity, a product sold by insurance companies. They’ll pay you a fixed income monthly so long as you live. The best part of annuities is you give up longevity risk: You’ll get the income even if you live to 120. The worst is that you are at risk from inflation, and the payouts are almost fixed in nominal terms. And payout rates are at record lows, because they are closely tied to the bond yields when you buy the annuity. A man aged 50 could convert $1 million into an income stream of $43,000 a year right now. But in 20 years’ time, even if inflation only averages a paltry 2% a year, that will only be worth $29,000 a year in today’s money.

The good news is that stock markets are flying high and plenty of people are making big money. But the outlook for a lifetime on Easy Street becomes harder when you look at converting the money into low-risk income.