This post was originally published on this site

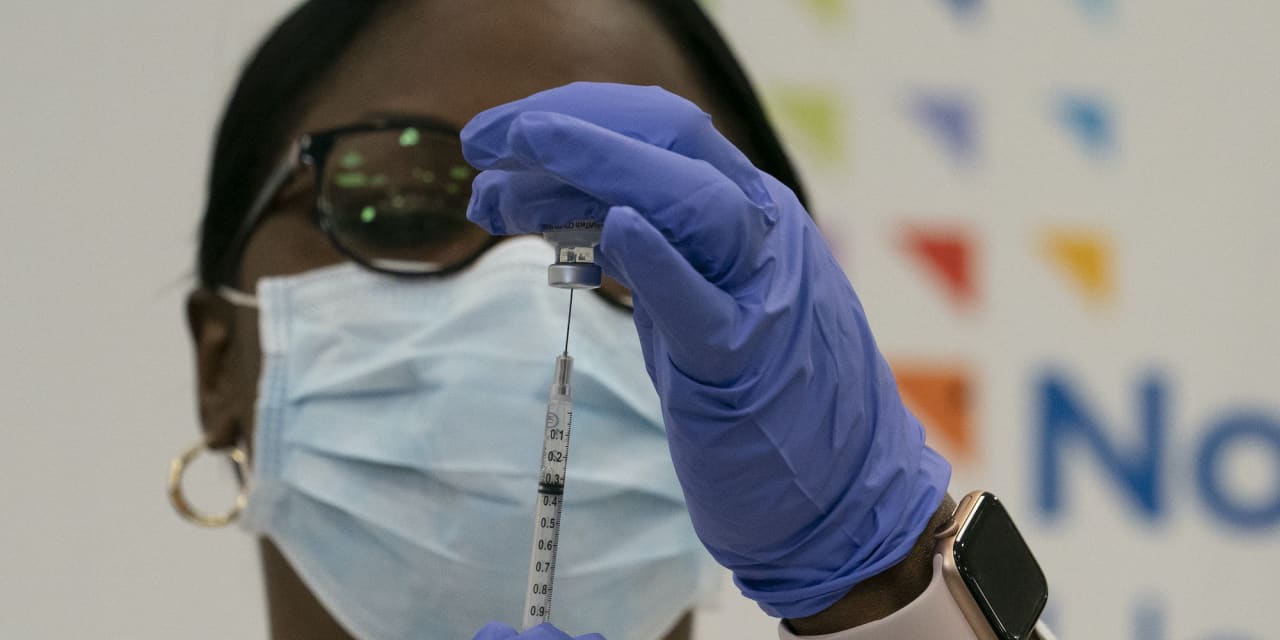

On Monday morning, one of America’s first Pfizer PFE, -1.40% vaccine doses was administered by Northwell Health, New York state’s largest health care provider. Intensive care nurse Sandra Lindsay was injected in Queens in the historic event.

The injection signals the beginning of the slow, laborious task of vaccinating millions of people in America’s most densely populated city, as New York battles a second, potentially devastating, wave of the virus.

“Today is V-Day in our fight against COVID-19,” said Michael Dowling, Northwell president and CEO. “This truly is a historic day for science and humanity.”

It follows the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorization on Saturday to utilize the Pfizer vaccine for emergency use. New York City will receive 170,000 doses in the initial delivery of the vaccine this week.

“Thank God, the cavalry is coming,” said Mayor Bill de Blasio during a briefing last week.

It is a cavalry that could not have come fast enough in a pandemic, which has claimed over 300,000 Americans and 1.5 million lives globally.

But with New York City experiencing a second wave of cases, prompting the decision by Gov. Andrew Cuomo and de Blasio to close down indoor dining again in the city from Dec. 14, what will the vaccine’s arrival mean for the average New Yorker?

Initially, for the general public at least, not a lot. With limited doses available, the vaccine will be distributed to health-care workers on the front line and nursing home residents, as per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines. Combined these two groups make up roughly 4% of New York state’s population.

Each person having the Pfizer vaccine will need two injections at 21 days apart.

“It makes sense to start with these groups because of their risk exposure,” said Carri Chan, an expert on hospital operations and professor at Columbia Business School.

Nursing homes have been among the hardest hit during the pandemic: residents and staff have made up roughly 39% of COVID-19 fatalities across the U.S., according to an AARP report. Meanwhile, Chan believes it is “ethically responsible” to protect high-risk health-care workers who are caring for the sickest COVID-19 patients.

“But, perhaps, more critically,” she adds, “staff is the bottleneck resource in treating patients with COVID-19. If our frontline staff are infected and unable to work, this jeopardizes the health system’s ability to care for the ever-increasing demand of COVID-19 patients.”

What will happen next — and who will be next in line — is less clear.

“I don’t believe a clear plan has been set up,” said Awi Federgruen, chair of the Decision, Risk, and Operations Division of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Business.

Federgruen argues that a combination of different factors should enter into deciding who is next in line: “Age, comorbidities, family size, household size, the nature of the person’s work — if they can’t work from home but need to work in a public arena. These are all factors that ought to go into some risk forum, by which one could then rank people. So that it’s not one single measure or one single metric that can be applied.”

New York state has indicated that it might next vaccinate essential workers (for example transport staff, grocery shop workers and police officers) and high-risk groups who have pre-existing conditions or are older.

Cuomo has also highlighted the toll that COVID-19 has taken on Black and Latino communities in New York, who have died at twice the rate of whites.

“We will have a very aggressive outreach plan that gets to Black and Latino communities, poor communities, using churches, using faith-based organizations. I’ve been working with the Urban League and the NAACP to do just that,” Cuomo told WAMC Northeast Public Radio last week.

Meanwhile, de Blasio has said that vaccination could be prioritized for residents of 27 New York City neighborhoods, mostly made up of minority communities, which have been disproportionately affected by the virus.

James Krellenstein, an organizer of the COVID-19 Working Group-New York, a coalition of health-care workers, advocates prioritizing additional vulnerable populations who are often forgotten.

“Our very large concern continues to be about prisons and other congregate settings like homeless centers, where the transmission risk is very high,” he said.

While the Pfizer vaccine is 95% effective — and the Moderna MRNA, -4.68% vaccine, which the FDA is expected to approve shortly, is 94% effective — there are still many unknowns.

Not least, whether they prevent transmission between people or only protect the person vaccinated. The former, experts believe, will be akin to sticking a Band-Aid on the pandemic; a solution that will help restrain the virus, but not eradicate it.

“We don’t yet know if these vaccines are stemming transmission,” Krellenstein said. “The second question is that we don’t know how long the duration [of vaccine protection is]. Do people need boosters?”

Third, Krellenstein said, scientists do not yet know how COVID-19 interacts in global settings: “Are there reservoirs of animals that can reintroduce the virus back into the human population?”

Given all these uncertainties, “it’s just extraordinarily important that people who are at a high risk of complications due to COVID are prioritized,” Krellenstein said.

As such, it is predicted that lower-risk adults may not be vaccinated until summer 2021. Those who have already had COVID-19 might also be vaccinated last, as it is assumed they will have some immunity(although how long that immunity lasts is not yet known).

Distribution, too, is a mammoth challenge in what many believe could become the largest — and certainly the fastest — mass vaccination campaign in American history.

While the Pfizer vaccine can be kept at 2 to 8 degrees Celsius for five days before its use, it needs to be stored prior to that at -75 degrees Celsius.

This will mean, initially at least, that vaccines will be distributed through hospitals which have ultracold freezers rather than local pharmacies or dedicated vaccinate centers.

Temperature requirements for the Moderna vaccine are less stringent. It can be stored at 2 to 8 degrees Celsius, the temperature of a kitchen refrigerator. Experts believe that when approved it should be sent to rural hospitals or other locations without ultracold freezers, such as prisons, pharmacies or the local doctor’s office.

Yet, Chan points to additional challenges in “keeping track of who has been vaccinated, who still needs a booster shot and when enough people in the current priority group have received their vaccine to open up to the next priority group.”

Ensuring that queues are minimized — perhaps through a reservation system — is also critical, so that vaccine centers or pharmacies don’t become transmission hotspots.

One of the largest hurdles to overcome, however, will be convincing the public to take the vaccine at all. In a Gallup poll performed in November, 42% of respondents in the U.S. said they would not get a vaccine. Social media has also spread unfounded and incorrect rumors, including that the Pfizer vaccine might cause infertility in women.

Krellenstein believes that a lack of government clarity is to blame. Mounting pressure by President Donald Trump on the FDA to approve the vaccine last week could also have led to a public perception that it was hurried out and is therefore not safe.

“I am a little bit alarmed by the communication with the public. Most members of the public simply don’t actually know what is going on,” Krellenstein said. “In any crisis management, clear, honest and transparent communications are imperative to solidifying public trust.”

While no serious issues cropped up during Pfizer’s trial of 44,000 participants, Krellenstein said it’s important for those vaccinated to know that there are some mild side effects — including headaches, fatigue and fever — to ensure no one panics post-vaccination.

“Both of these vaccines pack a punch,” he said. “You’re going to feel not particularly good: that message needs to be” sent out to the public.

Yet, he insisted, that while the trials were “done quickly, it does not mean it wasn’t done thoroughly. These studies that have been performed are extraordinarily large.”

For the vaccine to create herd immunity, it is estimated that 75% to 80% of the population needs to be vaccinated — a critical mass that may not be reached until the end of next summer, according to America’s top infectious disease doctor, Anthony Fauci. And that is, of course, only if the majority of the population agrees to vaccination.

For now, the message by authorities is simple: Stay vigilant, keep washing your hands and remain socially distanced, especially during the upcoming holiday period.

In New York —where total COVID hospitalizations are now at over 5,700 — that message particularly matters.

“We’ve got to get through December, January, and January into February,” de Blasio said last week. “This is the last big battle before us.”