This post was originally published on this site

Wall Street and Washington powerbrokers can no longer fully trust the government’s estimate of how many Americans are collecting unemployment benefits, but the jobless claims report is still useful as a signal of which way the wind is blowing.

“The levels are not worth spending a lot of time on,” said chief economist Stephen Stanley of Amherst Pierpont Securities, “but the direction of claims is reasonably important.”

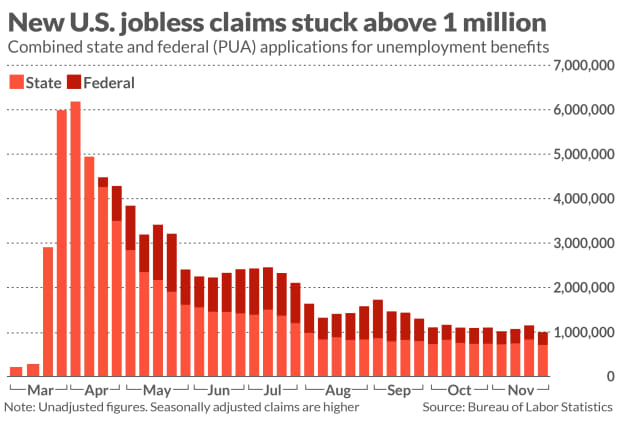

A government watchdog agency said last week U.S. jobless claims data has been rendered unreliable by a record deluge of applications during the pandemic that’s swamped state employment offices. Fraud, double-counting and inconsistent reporting standards have inflated the number of new and continuing claims, according to the General Accounting Office.

“The numbers [the Labor Department] reports for weeks of unemployment claimed do not accurately estimate the number of unique individuals claiming benefits,” the GAO said.

Read: Jobless claims inflated and inaccurate, GAO finds

Chief economist Scott Brown of Raymond James, who’s based in Florida, said problems are rife. “Here in Florida it’s been a real nightmare. These systems weren’t set up to handle millions of claims.”

The Bureau of Labor Statistics on Thursday is expected to report that initial jobless claims rose slightly to 720,000 in early December from 712,000 at the end of November. The total number of people receiving benefits — continuing claims — is expected to be around 20 million.

Neither of those figures is likely correct, the GAO report concluded, particularly continuing claims. The BLS totals don’t represent distinct individuals applying for or collecting benefits.

Economists have long suspected the jobless claims figures were inflated. One of the first to sound the alarm was Stanley, who declared as far back as June 18 that “I am officially giving up on jobless claims data.”

What made him suspicious was the big discrepancy between the level of unemployment as shown by continuing claims and the more accurate monthly jobs report.

The gap persists to this day.

While the claims report shows about 20 million people ostensibly collecting benefits, the monthly jobs report pegged the number of unemployed at 10.7 million at the end of November.

Stanley figures the weekly tally of continuing claims is off by several million, perhaps as many as 5 million.

“They are still very inflated, but they are moving down,” he noted.

Economists put a lot more trust in the monthly employment report, but it’s not perfect, either.

The number of unemployed, for example, is probably a bit too low because it doesn’t count all the people who dropped out of the labor force during the pandemic. The size of of the labor force has shrunk by 4.1 million to 160.5 million compared to the last month before the pandemic began.

“You look at the 6.7% unemployment rate and think it’s great,” said Brown, “but it’s probably a lot higher.”

What’s important to recognize, Brown said, is that even if the jobless claims figures are inflated, they are still historically high. And economists say that points to the need for more federal help from Congress, where lawmakers have been at an impasse for months.

“They need to allow these extended benefit programs to go until the pandemic is over,” Stanley said.

As for assessing the labor market itself, senior economist Sam Bullard at Wells Fargo said it makes sense to watch a range of indicators — a dashboard of sorts — to assess whether employment is getting better or worse.

Read: The 245,000 new jobs added last month is smallest since U.S. recovery began in May

What does he see? “Economic momentum is slowing as the year wraps up” due to the record rise in coronavirus cases and “attendant state and local restrictions.”