This post was originally published on this site

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers.

AFP via Getty Images

An all-star panel of economists implored Congress to pass a major new coronavirus stimulus package, with former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers making the argument that Washington politicians should become much more comfortable with large deficits and a growing national debt.

During a virtual event staged Tuesday afternoon by the Brookings Institute to advise the incoming Biden administration and Congress on fiscal policy, Summers attacked the conventional wisdom behind the bipartisan Simpson-Bowles fiscal responsibility commission created by President Barack Obama 10 years ago, when both Democrats and Republicans largely agreed that deficit reduction was urgently needed.

“Everyone was in agreement that having something like Simpson-Bowles would have been a good thing,” Summers said. “If that goal had been achieved the consequences would have been catastrophic.”

The panel also featured former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke; Jason Furman, the former chair of Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers; Olivier Blanchard, former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund; and Ken Rogoff, economics professor at Harvard University.

Each panelist agreed that fiscal deficits and rising debt should be tolerated, at least in the short term, both because of the coronavirus epidemic and related economic damage and because the U.S. government can borrow at negative interest rates, when accounting for inflation.

“We shouldn’t balance the budget anytime soon,” Bernanke said, and instead argued for taking advantage of historically low interest rates to finance investments in slowing climate change, providing health care and building infrastructure that would increase economic growth in the future.

Summers and Furman used the event to promote a new working paper, which advocates for updating the metrics that governments use to measure sustainability of their public debt.

The traditional method of comparing total government debt to a country’s GDP is “so misleading and problematic,” because total debt is a backward measure of a stock of financial assets, while GDP measures just one year of annual income.

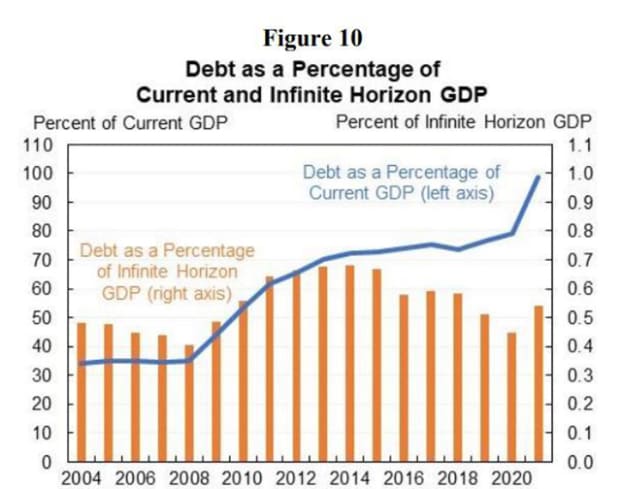

They argue a better measure would be to take net present value of all future GDP, which increases in times of low interest rates, and compare that to total debt. As the chart below shows, this measure has been stable over the past fifteen years.

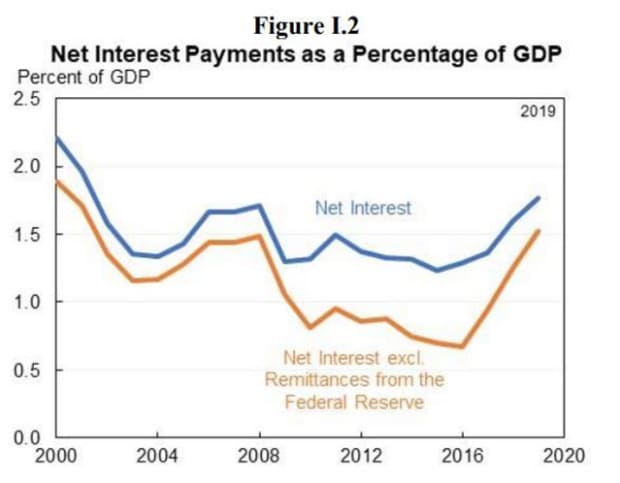

Another measure that better puts government debt into the context of very low interest rates is net interest payments as a percentage of GDP, Summers and Furman said.

In terms of the long-term sustainability of entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare, Summers said that adjustments should be made so that they don’t consume an ever-growing share of the federal budget. That said, demographic drivers of increased spending on Social Security are set to weaken in coming years, while Summers argued most of the problem could be solved by increasing payroll taxes on high earners.

Investors are eager for Congress to add to the federal debt with a new COVID relief package, with the S&P 500 SPX, +1.12% rising 1.1% Tuesday after news of a bipartisan proposal for $900 billion in new spending on aid for small businesses, state and local governments, schools and employment benefits, among other priorities.