This post was originally published on this site

Teamsters Union retirees protest deep cuts to their pension benefits in 2016.

Getty Images

In Ernest Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises,” Mike is asked how he went bankrupt. His reply: “Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.” He might as well be describing the prognosis for many of the nation’s 5,300 public pension funds, which hold $4.4 trillion in assets against what the Federal Reserve estimates to be $9 trillion in liabilities.

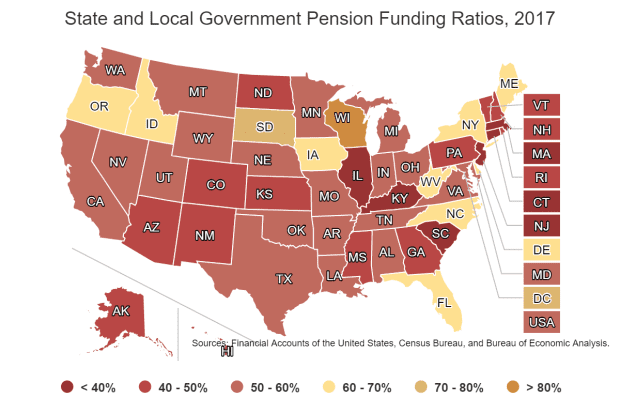

Most U.S. public pensions plans were in surplus in 2000. Today, based on their own accounting – which differs from that of the Fed – they hold less than 75 cents on every dollar they owe to their 33 million plan members. Funding gaps are now affecting municipal bond ratings, and COVID-19 has introduced new stresses to public finance.

Pension reform is needed, yet no one seems to know what to do. And few want to rock the boat.

We argue in a recently published study that there is a way out, even for public pension systems as deeply underwater as those in Illinois, Kentucky and New Jersey. The answer? Just look north to Canada to see what can be done.

Canada today has a public pension system that is well-funded and sustainable. This was not always the case. Until the late 1980s, its public pensions were in poor shape. During the inflationary 1970s, benefits were enhanced with retroactive indexation not matched with increased funding. Contributions were commingled with other public funds and lent to Provincial governments, not invested in markets. In some cases, Canadian provinces didn’t even have a good grip on the true actuarial value of their pension liabilities.

It eventually became clear to provincial finance ministers that failing to undertake comprehensive pension reform would imperil the retirement security of public sector workers. Current retirees might still receive their pensions, but younger workers would not. But protecting pensions would lead to higher taxes, pitting workers against taxpayers.

Elected officials implemented comprehensive reforms. Now – some 30 years later – that history should be required reading for elected officials of state and local governments across the U.S.

Reform does not mean simply finding new ways to invest money in search of higher returns. It is impossible to solve a pension fund’s problems solely through the investment portfolio. For one thing, almost every pension plan has negative cash flows, paying out more in benefits than it receives in contributions. Generating cash yield or holding cash balances are essential to funding benefits every year, but that drags down overall investment returns.

Moreover, many pensions unrealistically target annual returns of 7% or more. Most market strategists do not believe diversified pools of tens or hundreds of billions of dollars in assets can achieve that level of return decades into the future, particularly given today’s low interest rates. The target return is doubly important because it’s also the rate by which the stream of future pension benefit payments is discounted to the present. An excessive discount rate makes a pension fund seem more financially robust than it really is.

Instead, secure pensions require much more than spiced-up investing models. The basics: Acknowledge true deficits. Address past errors through catch-up funding. Align stakeholder interests through appropriate legal structures and governance. Ensure future sustainability through conservative plan design. Enhance investing offices. And mitigate long-term risk by matching fund assets to liabilities.

Five steps

Canada did all that. Here’s how.

First, actuaries were engaged to correctly value funding gaps which were made whole. In some provinces, taxpayers fully absorbed the cost of these gaps. In others, workers agreed to participate equally in bearing the cost.

Second, plans were reformulated under joint sponsorship of employer and employee interests. This gave employees a strong voice in determining the level of their benefits. It moderated that voice with the recognition of a shared burden for ensuring long-term plan sustainability: a seat at the table in return for skin in the game.

Third, the new legal structure led to more conservative funding models. Canadian pensions are designed conservatively. Contributions from members and employers cover about 80% of benefits in Canada compared with 55% in the U.S. While employer contributions are similar in the two countries, Canadian employees pay more into their pension systems relative to future benefits than do their peers in the U.S.

“ It is impossible to solve a pension fund’s problems solely through the investment portfolio. ”

Fourth, Canadian governments established sophisticated arms-length investment offices to manage pension assets. In the case of smaller plans, portfolios were pooled for more efficient management.

Fifth, pensions were oriented to investing with the objective of asset-liability matching. Today, they on average target 5.6% returns, compared with 7.2% in U.S. Despite this, Canadian pensions outperform those in the U.S.

Canadians prefer longer-duration assets such as directly-held real estate, toll roads and port facilities to generate the cash flows needed to pay promised benefits. They allocate a quarter of their portfolios to such “real assets,” compared to 10% in the U.S.

American public employee pensions tend to favor equity-risk strategies, since they need to “shoot for the stars” to achieve their challenging investment targets. Public and private equity and hedge funds comprise 60% of U.S. pension portfolios but only 41% of Canadian portfolios.

When done well, this strategy bears fruit. When not – or when markets do not oblige – the downside becomes substantial.

Pension reform in the U.S. will not come about without strong opposition. While the general consensus is that public pensions have strong protections in law, the calculus for unions – concerned about the welfare of both current and future retirees – would be to accept higher contributions today to protect benefits in the future. Otherwise it is increasingly likely that future workers would be shifted onto 401(k)-style defined-contribution systems or “shared risk” systems such as that in Wisconsin.

Finally, unions would want to prevent preemptive legislation that protects municipal bondholders and taxpayers in the case of potential pension bankruptcy, as happened in Central Falls, R.I.

Illinois has the worst-funded public pensions in America. Neighboring Wisconsin has designed its system around shared risk. Rather than pit taxpayers and workers against each other, this system formulaically adjusts benefits or contribution levels based on the value of assets relative to liabilities (benefits cannot fall below a minimum level). One is teetering on the brink of failure, while the other seems rock-solid and sustainable.

Is there a role for Washington in state and local pension reform? The Comptroller General of the U.S. has argued that “Congress should closely monitor actions taken by State and local governments to improve their plan funding to determine whether congressional action may be necessary.” That was in a report back in 1979. Inaction and tepid responses in the ensuing years to make needed public pension reforms mean that today, retaining and maintaining full funding levels could cost between 4% and 5% percent of state and local government tax revenues annually.

Continued foot-dragging will create additional burdens on future taxpayers and trigger unwelcome surprises for public-sector workers in their retirement years.

As the new administration begins to work with the states on their many public finance challenges, it should place public pension reform high on the agenda – and consider the imaginative actions that our northern neighbor undertook some 30 years ago.

Ingo Walter is a professor emeritus of finance at NYU Stern School of Business. Clive Lipshitz is managing partner at Tradewind Interstate Advisors and a guest scholar at New York University.