A crew works to repair a road destroyed by flooding in 2018.

Getty Images

The year 2021 may be the time for lawmakers in Washington, D.C. to modernize how we pay for our roads.

Federal motor fuel taxes, which are supposed to cover federal highway and transit spending, no longer raise enough revenue to do so and have lost ground as an effective measurement of how much drivers use public roads. This shortfall is expected to grow even bigger as more people drive hybrid or all-electric cars, which don’t pay (or pay much) in fuel tax but still add to the wear and tear on roads.

A popular and more equitable solution, long supported by economists, is to base the tax on miles driven — VMT — rather than taxing gallons of fuel or vehicle type in an effort to estimate drivers’ use of transportation infrastructure.

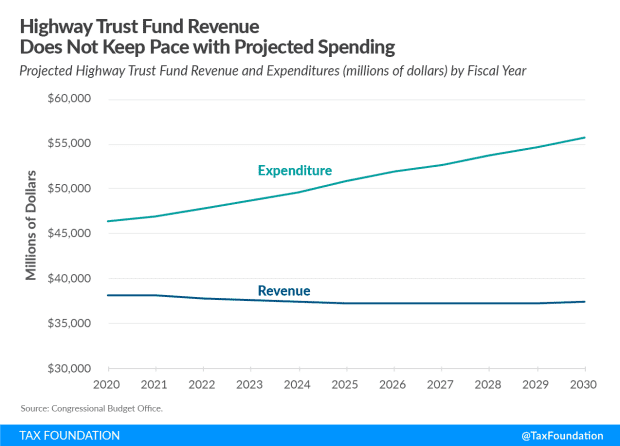

Expenditures have exceeded revenues for over a decade, and even before the coronavirus pandemic, Congressional Budget Office projections showed that gap widening substantially. The gap between revenue and expenses was just over $8 billion in 2020 and is expected to grow to roughly $13.5 billion by 2025. Given how COVID-19 has hurt the economy, actual shortfalls will almost certainly be worse. Without additional funding from other tax revenue sources (current funding expires in 2021), the deficit is expected to grow to $70 billion over five years.

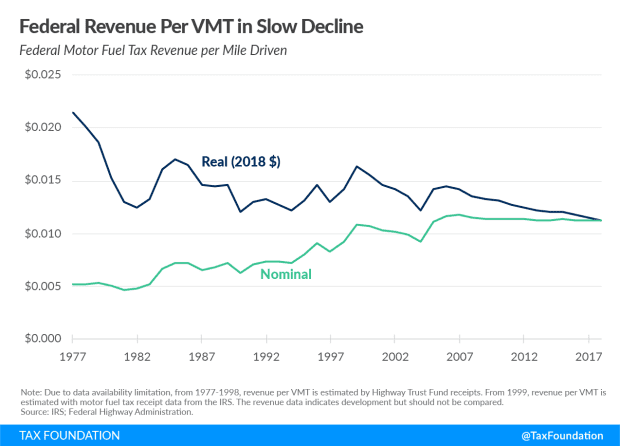

A major reason for the widening gap is improved fuel efficiency. Since cars drive farther on a gallon of gas today than in 1993 (the last time the federal gas tax was increased, to 18.4 cents per gallon), tax revenue collected per vehicle mile traveled (VMT) has declined in inflation-adjusted terms.

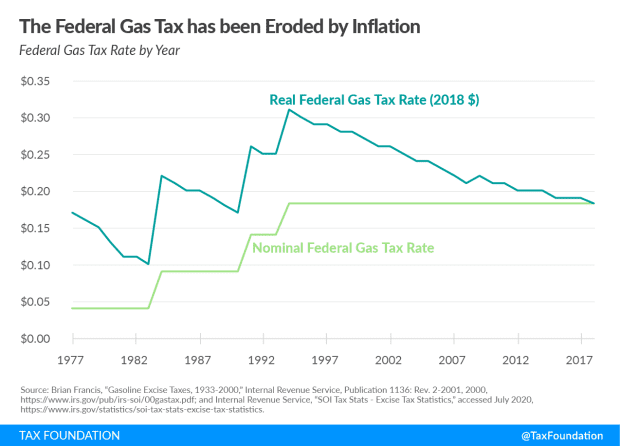

Moreover, inflation means these dollars don’t buy as much highway maintenance as they did 27 years ago. Even if vehicles didn’t get better mileage today, the 1993 tax rate of 18.4 cents per gallon would need to be more than 30 cents per gallon today to have the same purchasing power. States have faced a similar issue, but unlike the federal government, many have increased their gas taxes in recent years.

Finally, the growth in electric vehicles sales could eventually make the motor fuel tax an anachronism.

The federal government’s current transportation funding legislation, the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act, was set to expire this year but has been extended another year.

It is understandable that Congress punted the issue to 2021 given the coronavirus pandemic. However, it will get harder and harder for the White House and Congress to ignore this problem. Given ever-more-frequent calls for spending more money to repair and replace America’s roads and bridges as part of a stimulus package, this is an opportunity for lawmakers to reconsider how we pay for infrastructure.

How a VMT tax would work

A tax levied on miles traveled, rather than a tax on a gallon of gas, gets much closer to approximating each driver’s share of repairing and repaving the roads.

Of course, it is not that simple politically. A VMT tax that raised enough revenue to cover federal spending would be a net tax increase: in 2018, highway fund outlays were $55 billion, and Americans covered 3.225 trillion miles in their vehicles. That translates into a VMT tax of 1.7 cents per mile, or an average federal VMT tax bill of about $200 per vehicle, given that the average vehicle traveled 11,843 miles. Instead, the average amount paid in motor fuel taxes was roughly $120.

Increased taxation of the owners of electric vehicles and fuel-efficient cars would also create political challenges. These drivers would experience a larger tax increase while drivers of less-efficient cars could see a smaller increase.

In practice, a VMT tax could be implemented by either levying a flat fee or developing a more advanced tracking system with different rates. A flat fee per mile (taking the vehicle’s weight into consideration) measured by the vehicle’s odometer would be the simplest version. Odometer readings could be done at yearly inspections or by installing an on-board unit that electronically transmits VMT to a central computer.

The problem with a simple solution is that it severely limits how the tax can account for important differences in travel. For instance, the existing problem of effectively taxing the use of non-public roads (private roads or farmland) would persist. It also makes it difficult to accurately allocate money among any states that replace their own gas taxes with a VMT plan, which many would likely do if the federal government provided the necessary framework.

Solving these problems would require that both miles traveled and location are tracked, while making it possible to charge a higher rate on, for example, urban travel as opposed to rural travel. A VMT would thus account for differences in contribution to air pollution and congestion.

While critics could argue that shorter commutes would be punished compared with longer rural ones, congestion-prone urban areas would benefit too. Increasing the cost of driving in urban areas would, in all likelihood, limit demand resulting in fewer vehicles on the road.

States could also impose taxes on miles traveled in their own state, regardless of where the driver resides.

While a VMT tax with a GPS tracking is more efficient, there are legitimate privacy concerns. According to a Government Accountability Office analysis from 2012, 45 out of 51 state DOT officials (including Washington, D.C.) said addressing privacy-related concerns would present a great challenge to developing a VMT tax program in their state.

As an example of unintended use of traffic data, information from E-ZPass, an electronic toll collection system, has been used by divorce lawyers to demonstrate spousal unfaithfulness.

Despite these challenges, a VMT tax is an equitable, long-term and promising option for replacing motor fuel taxes as the funding mechanism for transportation spending in the future.

Ulrik Boesen is a senior policy analyst with the Center for State Tax Policy at the Tax Foundation, a Washington, D.C. think tank focused on tax policy. Follow him on Twitter @UBoesen