This post was originally published on this site

Earlier this year, investors appear to have run from money market funds before the protective gates could be triggered. Now, new regulation may kick in.

AFP/Getty Images

Stung by the second severe market selloff in a decade that required the federal government to come to the rescue, financial market regulators are looking at additional reforms of Wall Street.

This time, with COVID-19 hobbling the economy and markets stressed especially early in the crisis, it’s the non-bank sector under the microscope. In 2008, it was the “too-big-to-fail” bank sector that got the brunt of the attention from Washington.

One thing that the two financial crises have in common is that investors ran from money market funds at the first hint of trouble. The outflows put stress on the entire system of short-term funding, such as municipal finance.

In 2008, investors didn’t know if the money market funds held commercial paper issued by Leman Brothers and fled for the exits.

In the wake of this run, after a tortious regulatory process, the Securities and Exchange Commission mandated the money market funds put up gates to suspend redemptions or impose fees.

In 2020, investors appear to have run from money market funds before the gates could be triggered.

Read: Prime money-market funds, could they disappear

The Fed, which spent over $2 trillion to stabilize the financial system in the wake of the pandemic, set up a loan program specifically to help money-market funds.

Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren, a leading advocate for reform of money-market funds, has seen enough.

“My personal preference would be not to have prime money market funds,” for either institutional or retail customers. Rosengren said in a talk at Harvard’s Kennedy School earlier this week. Money-market funds that invest in government securities should not be punished.

Efforts to reform the sector “was not very successful,” he said.

Feeling the heat, the mutual fund industry is gearing up for a regulatory skirmish. The home page of the Investment Company Institute, the industry’s lobbying arm, has a 52-page research note entitled “Prime money market funds didn’t trigger financial turmoil in March.”

The industry is concerned about a rush to judgement, said Sean Collins, chief economist of the ICI in an interview.

“Our view… is it is really important to keep in mind that everything that happened, happened because of the virus. That has to be the starting point,” he said.

“Jumping right to money-market funds… that’s a big leap. There were issues across the globe, across all markets,” he said.

The starting point for regulators should be how to make markets “in general” more resilient, he added.

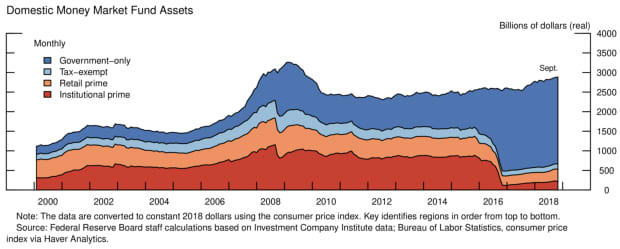

Institutional and prime money market funds amount to a small amount of the total industry.

The ICI noted that money market funds never activated gates or fees and agrees that investors did seem to run for fear that they would be imposed despite industry efforts to educate investors that they were optional.

Ian Katz, a director and financial policy analyst at Capital Alpha Partners didn’t hear Rosengren’s remarks but said he doubted the eventual reform would end with the disappearance of prime funds entirely.

“Something will be done, but I don’t expect the entire product to be eliminated,” Katz said.

The money-market fund issue may be an early test of how aggressive the new Biden administration approaches Wall Street reform.

In Washington’s complicated regulatory stew, money-market funds are under the SEC’s jurisdiction.

That’s the agency where the regulatory action in the wake of the March selloff ought to be, said Dan Tarullo, a former Fed governor who was the point man on financial market reform in the wake of the financial crisis.

Eliminating prime money market funds would take an SEC rulemaking process that could take years.

Biden appointees at the SEC have a “big unfinished agenda” of designing updated regulation for hedge funds and mortgage REITs, as well as money-market funds, Tarullo said in an interview on Bloomberg.

“It’s not one of simply rolling back what the Trump people have done. It’s actually doing something that has been crying out for attention for quite some time,” Tarullo said.

Wall Street experts were divided on how prime money-market funds would fare.

“To some extent, I do think that prime MMF are on borrowed time. They are facing increasing regulatory pressures and the commercial paper market is a shell of its former self,” said Nick Maroutsos, head of global bonds at Janus Henderson, in emailed comments.

Jerry Klein, head of corporate cash management at HighTower Treasury Partners, thought that prime money market funds would continue to have a role in the market.