This post was originally published on this site

Many Americans steered clear of hospitals early in the pandemic for fear of contracting the coronavirus.

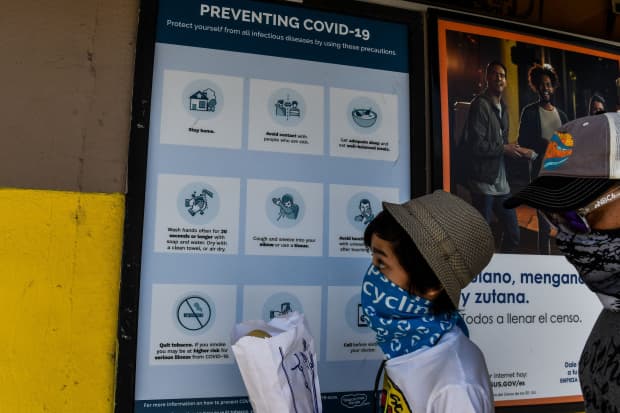

Chandan Khanna/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

Amid shelter-in-place orders and school closures aimed at stemming the spread of COVID-19, the share of children’s emergency-department visits related to mental health has risen substantially during the pandemic, a new U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report says.

From mid-March through October, the proportion of mental health-related emergency-department visits increased by about 24% for kids aged 5 to 11 compared to the same period in 2019, the report said, and increased by 31% for kids aged 12 to 17.

“Many mental disorders commence in childhood, and mental health concerns in these age groups might be exacerbated by stress related to the pandemic and abrupt disruptions to daily life associated with mitigation efforts, including anxiety about illness, social isolation, and interrupted connectedness to school,” the authors wrote.

The analysis’s findings, they added, “demonstrate continued need for mental health care for children during the pandemic and highlight the importance of expanding mental health services” such as telehealth and mental-health apps.

COVID-19 restrictions have also reduced or changed children’s access to mental-health services that are normally available to them through schools and other community entities, the report said, and might lead to greater reliance on emergency-department services “for both routine and crisis treatment.”

The CDC analyzed hospital data in 47 states, representing around 73% of emergency-department visits in the U.S. Potential study limitations included that National Syndromic Surveillance Program emergency-department data, the subject of the analysis, isn’t nationally representative and may not have produced broadly generalizable findings; usable race and ethnicity data were also unavailable.

“ Child mental-health professionals say parents should monitor their children for major behavioral changes, contact a health-care provider if a change in the child’s behavior is persistent and starts impacting their ability to function, and avoid trying to diagnose mental-health conditions in kids on their own. ”

The heightened share of children’s mental health-related emergency visits during the first several months of the pandemic could be inflated due to the sizable decline in overall emergency-department visits during that time, the report said. Many Americans steered clear of hospitals for fear of contracting the coronavirus.

But while the overall number of emergency-department visits related to children’s mental health declined during the pandemic, the proportion of such visits increased, the report noted — context that suggests “children’s mental health warranted sufficient concern to visit [emergency departments] during a time when non-emergent ED visits were discouraged.”

Previous research has highlighted the pandemic’s impact on children’s and parents’ mental health. One study published in the journal Pediatrics, for example, analyzed surveys from February to April of hourly service workers with a young child and found that “in families that have experienced multiple hardships related to the [COVID-19] crisis, both parents’ and children’s mental health is worse.”

Another study published in the same journal, based on a June survey of parents with children under 18, found that “27% of parents reported worsening mental health for themselves, and 14% reported worsening behavioral health for their children” since March.

Child mental-health professionals say parents should monitor their children for major behavioral changes, contact a health-care provider if a change in the child’s behavior is persistent and starts impacting their ability to function, and avoid trying to diagnose mental-health conditions in kids on their own.

“We should expect that some kids likely will have some changes in their behaviors and their moods,” clinical psychologist Garica Sanford, the training director at the nonprofit Momentous Institute in Dallas, Texas, previously told MarketWatch. “But we really want to look at severity, frequency and duration of changes.”

For more information on how to keep tabs on your child’s mental health during COVID-19 and get them help if needed, check out MarketWatch’s guide here.