This post was originally published on this site

Turkeys at Ferndale Market in Cannon Falls, Minn. Smaller-than-usual Thanksgiving gatherings this year are expected to fuel demand for smaller birds.

Photo courtesy of Ferndale Market

When retailers first started placing orders this summer for their share of the roughly 30,000 free-range antibiotic-free turkeys that John Peterson’s farm, Ferndale Market, produces each year, they had a request particular to our pandemic era: Smaller turkeys.

Betting that many families would be deterred by public health guidelines from gathering the full complement of relatives at their Thanksgiving table this year, the retailers asked Peterson for more 10- to 14-pound birds than typical.

But there was little Peterson could do to adjust to the demand for smaller, fresh turkeys. The birds had already started growing by the time retailers were placing their orders. The farm couldn’t process the turkeys earlier. because that would mean they would be on the shelf for too long to be sold fresh. So Peterson and his team in Cannon Falls, Minnesota, did their best to meet retailers’ demands with frozen turkeys. But when it comes to the fresh birds, “we’re boxed in by the calendar,” Peterson said.

“We’ve said no to more things than we would in a normal year,” Peterson said.

John Peterson, the owner of Ferndale Market.

“It’s really hard to pivot in agriculture, we’ve been reminded of that this year when everyone is talking about pivoting,” Peterson added. “We’re dealing with nature, we’re dealing with a living creature that takes months to grow.”

Consumer demands at odds with how turkeys have been raised for decades

Like everything that’s taken place during the coronavirus pandemic, Thanksgiving is likely to look different for many families than in a typical year. Indoor gatherings of groups of family and friends have been linked to increasing COVID-19 positivity rates across the country — evidence that will convince at least some households to limit their Thanksgiving celebration to those living in their home. Thirty percent of respondents to a survey conducted by Butterball SEB, +0.56%, the poultry company, said they are hosting only immediate family this year, up from 18% in a typical year.

Given those trends, demand for turkeys sized more appropriately for groups of two, four or six people makes sense. But it runs counter to how commercial turkeys have been raised over the past few decades.

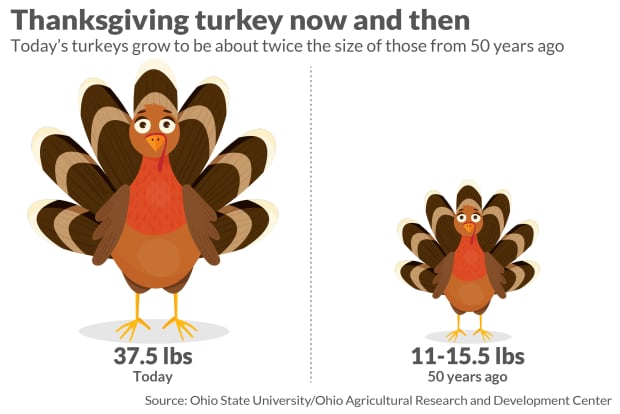

“The story that I usually tell is that the commercial bird of today basically grows to double the weight in half the time,” said Gale Strasburg, a professor in the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition at Michigan State University.

That’s largely because the economics of raising small turkeys aren’t great. For one, the fixed costs involved in raising a 10-pound bird are largely the same as those involved in raising a 20-pound bird, but because a customer typically pays the same price per pound of meat regardless of the size of the turkey, the fixed costs go further with larger turkeys.

In addition, large commercial turkey operations are raising the bulk of their turkeys to sell as part of processed meat products, like deli or ground meat, Strasburg said. Over the past few decades, commercial turkey producers have selectively bred their turkeys to have large breasts, which allows them to produce the most valuable part of the turkey efficiently in an environment of thin margins, he said.

“It’s actually gotten to be a little bit of a problem because the birds have gotten to be so big and so heavy so that in some cases you run into skeletal problems,” Strasburg said. “The legs aren’t strong enough to hold up the bird when it gets to be so gigantic.”

The growth in both turkey size and number of turkeys produced began ticking up in the 1970s as demand for poultry increased amid a shift away from red meat, Strasburg said. Production has leveled off since roughly 2010.

Retailers are betting on a desire for smaller turkeys

The pandemic may have accelerated a trend towards smaller birds that was already taking place, said Darren Ference, the chair of Turkey Farmers of Canada. Ference, who has been raising turkeys in Alberta, Canada for 20 years, said that in the past four or five years, he’s seen increased demand for smaller turkeys and for turkey parts, in part because of changing consumer habits.

In Canada, where residents celebrated Thanksgiving on Oct. 12, early data on what producers sold to retailers suggests that smaller birds, as well as parts, were popular, Ference said.

Retailers in the U.S. appear to be betting on this trend continuing here. At Walmart WMT, -1.53%, stores have increased their assortment of turkey breasts by 20% to 30%. Baldor Specialty Foods, a New York City-based food distributor, also upped its orders for small turkeys this year.

“Just based on the shutdowns and the very minimal service at country clubs and catering just sort of bottoming out, it was clear that there was going go to be a run on small turkeys this year,” said Sophie Mellet-Grinnell, the meat and poultry specialist at Baldor Specialty Foods.

“ ‘It was clear that there was going to be a run on small turkeys this year.’ ”

“We were right. That’s the first thing we sold out of,” she said. “There are some people that are going to end up with a 20-pound turkey because they ordered late.”

Though producers are working to meet retailers’ requests for smaller turkeys, there’s only so much they can control, at least when it comes to fresh turkeys, Mellet-Grinnell said. There’s a limit to how many turkeys can be processed in each day and every day a turkey isn’t processed is another day that it grows.

At Rettland Farm in Gettysburg, Penn., processing the birds earlier than typical wasn’t an option, given that the market for their roughly 150 turkeys is seeking fresh, not frozen turkey, said Beau Ramsburg, the farm’s owner. Instead, they started raising their turkeys a little bit later in the season, a decision they came to earlier this summer.

“It has largely proven to be a decent idea,” he said. “We’ve had plenty of people telling us that smaller is OK this year, as opposed to people telling us that we don’t have birds big enough for them.”

Pandemic has increased interest in specialty turkeys

Though size will likely be the No. 1 factor driving households’ turkey-buying decisions, according to Mellet-Grinnell, she’s seen other changes to the way families are approaching their Thanksgiving meal this year. She’s seen an uptick in interest in specialty birds, like heritage turkeys, a group of turkey breeds that were in production before the industrial revolution and are raised for long outdoor lives. These birds tend to be smaller than the bulk of turkeys produced commercially nowadays.

Mellett-Grinnell attributes the increased interest to the greater understanding consumers have gained about their food during the pandemic as they’ve been forced both to cook more and to source their ingredients directly instead of heading to stores frequently.

“ ‘The birds have gotten to be so big and so heavy so that in some cases you run into skeletal problems.’ ”

At Doko Farm, which raises about 40 heritage turkeys each year in Richland County, S.C., the customer mix this Thanksgiving has been different than in previous years, said owner Amanda Jones.

Typically she sells the bulk of her turkeys to her local farmers market customers, but this year, “I have people driving three hours one way to pick up a turkey and then go back home again,” she said. Jones thought she’d have some turkeys left over to sell as prepared parts; lemon-pepper wings or sausage, for example. But instead, she’s sold out.

“Everything has kind of slowed down a bit and people are willing to try new things,” she said. Doko Farm is providing guidance for those new to heritage turkeys on how to cook them to maximize flavor (the strategy can vary slightly from cooking a commercial bird).

Shipping turkeys nationwide for the first time

At Ferndale Farm, turkeys may travel farther this Thanksgiving than they have in the past, Peterson said. The pandemic both increased interest from consumers in buying directly from farms and necessitated that Ferndale create a system for local customers to easily drive-through and pick up their turkeys. Those factors inspired the farm to create its first-ever consumer online ordering system.

The households Peterson sells to directly are still demanding larger turkeys, he says. That — as well as the possibility of selling turkey parts — has made him confident that the farm will still sell roughly 30,000 turkeys this year, even if it couldn’t provide as many smaller turkeys as retailers demanded.

“If folks are going to have a smaller gathering, maybe rather than buying a small 10-pound turkey, they might buy two thighs and a breast and call it a day,” he said. “The pandemic has shown us that people are really valuing tradition and they’re valuing time together with loved ones whatever that might look like.”