This post was originally published on this site

The Sherwin Family Winery burned from Glass Fire, sparked Sept. 27.

Sherwin Family Vineyards

Dario Sattui has seen a lot in his half-century in the wine business, but never a year as brutal as this one.

“First of all, we had the COVID shutdowns for three months. Then, after the first fires in the hills, visitors didn’t come,” Sattui, 78, said of blazes in August that converged nearby into the LNU Lightining Complex fire, the fourth-largest in California’s history.

That was before the Glass Fire struck the Napa Valley region, and became the most destructive in the history of the fabled California wine country. The blaze, sparked on Sept. 27, burned 67,484 acres and destroyed hundreds of homes.

For Sattui, the Glass Fire destroyed an estimated $9 million worth of wine and ravaged his stone farmhouse, but left his iconic Castello di Amorosa winery in Calistoga unscathed. But business has been slow to return, and he sees struggles all around for local businesses, from restaurants to beauty parlors to motels catering to tourists.

“In 48 years in the business, this is, by far, the most horrific, devastating and catastrophic year.”

The farmhouse at Castello di Amorosa in Calistoga, Calif.

Castello di Amorosa

Sattui already has begun plotting out the restoration of his farmhouse, down to its handmade roof tiles from Europe. His Tuscan-style castle Castello di Amorosa also reopened to visitors about a week ago. But despite the return of blue skies across Napa’s billion-dollar wine region, Sattui said the castle only has seen about a third of the visitors from the same month last year.

“Most of what burned was in the hillsides,” Sattui said. “Napa really makes great wine. I want to encourage people to come and visit.”

Napa’s wine region consists of 46,000 acres under cultivation, but with its hotels, restaurants and other tourism-related businesses, it provides an estimated $9.5 billion annually to the local economy and $34 billion nationally, even though its crop production accounts for only about 4% of California’s wine grapes.

Jon Moramarco, managing partner of wine analytics and advisory company bw166, estimates that the Glass Fire’s property damage alone, with nearly three dozen Napa Valley wineries hit, could total hundreds of millions of dollars, while lost wine inventory could add another $20 million to $50 million.

Crop damage from smoke and fire, per his estimates, could also threaten up to one-third, or about $200 million worth, of the region’s wine grapes and deal an $800 million blow to wineries’ revenue over time.

“Unfortunately, we’ll know more when the grape crush reports come out in February,” he told MarketWatch.

Mountains see brunt of fire

The hardest-hit areas from the Glass Fire were the wine grape-growing regions of Howell Mountain and Spring Mountain, which like many of Napa Valley’s hundreds of wineries, typically are family run and produce fewer than 10,000 cases of wine a year.

Matt Sherwin said his parents’ home in Spring Mountain was fine, since the vineyard acted as a firebreak, but that the family’s 24-year-old Sherwin Family Vineyards winery, which burned and collapsed into the cellar and barrel storage area, was a total loss.

“Basically, we lost 2019 and 2020,” the assistant winemaker told MarketWatch, adding that sales of its older vintages bottled and stored off-site will help sustain the business as they rebuild.

“It is one of those things where we won’t feel the pain from the lost vintages immediately,” he said. “We won’t feel that for three years, when there’s a big hole for the two years where we won’t have anything.”

Steve Sherwin sifts through rubble at his family winery.

Sherwin Family Vineyards

David Nassar, a co-founder of the destroyed Flying Lady Winery on Spring Mountain, also plans to rebuild.

“My private collection, including the ’15 and ’16 vintages and virtually all of 2017 burned in the fire. That was the missile shot for us,” he said.

Burned bottles lie amid the rubble at Flying Lady Winery.

Zachary Nassar

But the former MarketWatch columnist said that Flying Lady’s 2018 and 2019 vintages were aging in a nearby cave and undamaged, meaning the brand will continue as they rebuild.

“We look at this as an unfortunate risk that hit us,” Nassar said. “It will not keep us down.”

Despite the fire’s destruction, Linda Reiff, president and chief executive of Napa Valley Vintners, stressed that about 80% of the group’s 550 winery members plan to move forward with their 2020 vintage.

“It is too soon to speculate on volume, yet we can say it will be smaller than usual,” Reiff said in emailed commentary, adding that only wine worthy of the Napa Valley label will make it into the bottle.

Kathryn Hall, owner of Hall, Walt and Baca wines, who is raising funds for wineries impacted by the Glass Fire, said that for this year’s vintage, it’s likely going to play out in terms of “quality, instead of quantity.”

“I don’t think we will ever recover this tourism season,” Hall said, pointing to the economic toll of the coronavirus pandemic on hotels, restaurants and wine-tasting rooms. “But folks are coming back. That’s been really encouraging.”

Even before the fires, Moramarco at bw166 in April pegged the pandemic’s toll as potentially costing the nation’s nearly 10,000 wineries up to $5.9 billion this year, with the biggest drain being reduced tasting-room sales.

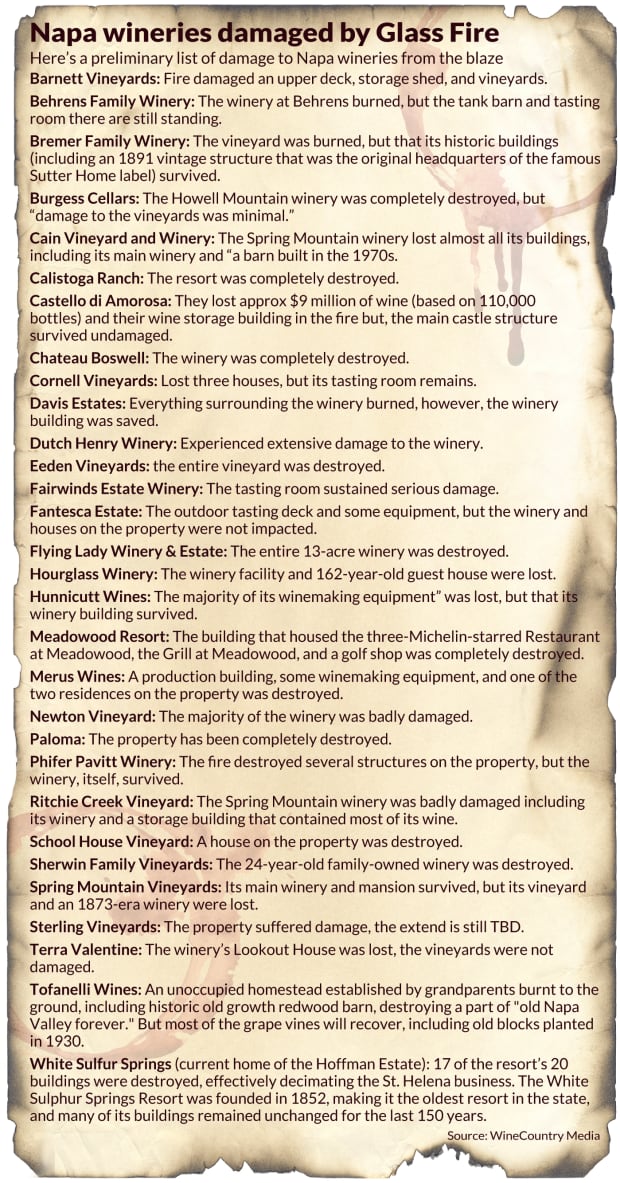

The Glass Fire could add another $1 billion in losses for wineries. Here are details of its known damage:

Glass Fire’s toll

WineCountry Media, additional reporting by MarketWatch

Smaller wineries that make up the bulk of the American wine business are likely to have been the hardest hit by the pandemic, due to their heavy reliance on travel and tourism for sales, rather than distribution to customers through big-box retailers.

Related: How the pandemic is upending business in wine country

The Wine Institute’s Gladys Horiuchi said people hear about California’s devastating wildfires and have the misconception that the entire 2020 “vintage is lost,” even though most of the West Coast’s wineries, from Washington state to the border with Mexico, were untouched by fires.

“They are open for business, but of course you have COVID issues,” she told MarketWatch, adding that COVID-19 means tasting rooms must operate at half capacity, which has pushed many of the nation’s winemakers to focus more heavily on digital sales and online wine tastings.

But if you ask Napa’s winemakers, it’s about moving forward despite hardship.

“My father was a farmer,” Hall said. “I think it’s in our DNA to roll with the punches that nature gives you.”