This post was originally published on this site

Only one in every 1,000 California residents has been able to get through to the state’s Employment Development Department phone line, according to a strike team report.

MarketWatch photo illustration/iStockphoto|, Getty Images

Christine White filed for unemployment on March 30, two weeks after her home state of California entered shelter-in-place due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and didn’t hear back for a month.

That’s when she started calling and emailing the state’s Employment Development Department.

“I’m in sales, so I’m pretty persistent,” White said. “On any given day, I was calling 70 times in a row. One time I was on hold for eight hours — around 6 p.m. or 7 p.m., they stopped taking calls. I got a message saying they were closed. I cried.”

White, of Vallejo, Calif., spent nearly three months trying to get her benefits, which caused her to stop paying rent and request food stamps to avoid going hungry. It wasn’t until she started contacting state senators in June that she eventually heard back that her claim had been approved and the checks started coming.

She still considers herself lucky.

Christine White

Christine White, pictured, waited nearly three months to receive her unemployment benefits.

“I know so many people who couldn’t even get past a phone call” because the wait times were so long, White said.

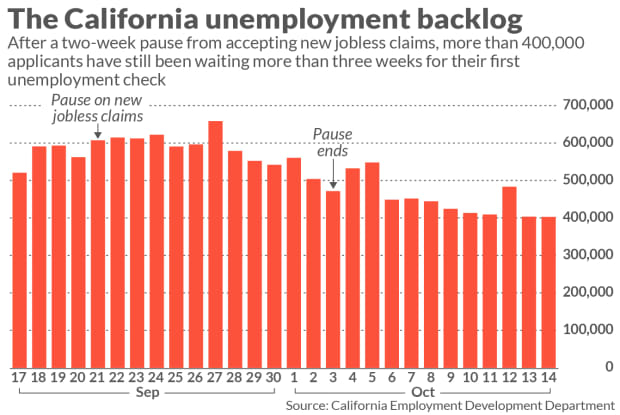

White’s story has been a common one in California throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, as the California EDD has reported backlogs of residents who filed a first-time unemployment claim has built as high as 658,565 on Sept 27. That’s equivalent to the population of Portland, Ore.

The state reported that backlog during a two-week pause on new applications in an attempt to catch up to the backlog that had been mounting for weeks prior.

“ California EDD has reported backlogs of residents who filed a first-time unemployment claim has built as high as 658,565 on Sept 27, equivalent to the population of Portland, Ore. ”

The pause began on Sept. 21 and lasted until Oct. 3, a period that coincided with Walt Disney Co. DIS, -0.43% announcing 28,000 layoffs of theme-park employees, who could not immediately apply for relief.

An update on Thursday showed the backlog had fallen by 39% thanks to the two-week pause, but 402,755 Californians were still waiting for their first checks more than three weeks after initially applying.

The core reason for the failures at EDD, according to a report from a “strike team” established by Gov. Gavin Newsom in July, was a focus on catching those attempting to defraud the system instead of helping residents obtain their benefits.

“EDD had a culture of prioritizing fraud above all else,” Assemblymember David Chiu, D-San Francisco, told MarketWatch.

Nationally, all state workforce agencies have dealt with an unprecedented amount of fraud during the pandemic. This was especially true after Congress passed the CARES Act which enabled jobless Americans to collect an additional $600 a week in unemployment benefits on top of what they would have otherwise received from their states.

“ ‘EDD didn’t catch sophisticated fraudsters, and they prevented honest Californians from getting benefits. It was the worst of both worlds.’ ”

Washington state took a two-day pause in paying claims in May after a federal investigation determined that a Nigerian-based criminal ring called Scattered Canary allegedly used stolen Social Security numbers and other identifying information needed to file for unemployment benefits in multiple states including Washington. The department so far has been able to recover $346 million of the $576 million illegitimate payments that were made.

In California, EDD throughout the pandemic has sought to proactively avoid having to recover illegitimate payments “by flagging claims for further identity verification,” the strike team report found.

But doing so has contributed to 78% of the manual processing EDD staff has undertaken during the pandemic, according to the report. Over the course of May, June and July this year “EDD routed 1,383,302 claims through manual processing, primarily to further validate their identity, in the hopes of flagging what appears to be .02% of claimants who can be identified as imposters.”

Some claimants are mistakenly flagged for fraud “for things like not including their middle initial in their claim but their middle initial is on their driver’s license,” said Andrew Stettner, a senior fellow at the liberal-leaning Century Foundation.

“EDD didn’t catch sophisticated fraudsters, and they prevented honest Californians from getting benefits,” Chiu said. “It was the worst of both worlds.”

How California is trying to fix its system

Before the strike team began working on its 45-day investigative report on improving EDD, Newsom promised to deliver better service to Californians. The two-week pause on new claims, which was recommended by the strike team, angered residents. But it was given the green light to allow the state to make adjustments that likely would not have been possible without a pause,

One of the major changes EDD implemented was a new identity-verification technology, ID.me. “This not only serves to help us prevent the occurrence of fraud at the onset of a claim, but it will also will allow us to more quickly authenticate legitimate claimants and help EDD process their claims faster,” Loree Levy, Deputy Director at EDD, told MarketWatch in a statement.

State workforce agencies are required to report to the Department of Labor that no more than 10% of unemployment insurance payments were made improperly. To satisfy the requirement, states must detect potentially fraudulent jobless claims filings coming from people who seek to impersonate other people to collect benefits.

ID.me was also implemented to help reduce the share of claims that require manual processing. Prior to the two-week pause, some 40% of claims needed to be processed manually, the strike team report found. That matters because “once you require manual processing, you cannot have your claim determined in under 21 days,” states the report.

ID.me was supposed to increase the share of claims that could be automatically processed from 60% to 91%.

“We learned just a few days after the system came online, they [EDD] were only automatically processing 64% of applicants,” Chiu said citing an EDD report published on Oct. 7. “So they’re woefully below where they thought they would be.”

Levy said “we anticipate the consistent liquidating of the backlog over the next few months.”

The system’s outdated technology provided one of the biggest challenges for EDD as it tried to modernize its system amid the surge of applications during the pandemic. Like many state workforce agencies, California’s state unemployment system was built using software that runs on a coding language known as COBOL, which was invented in the late 1950s.

Most of EDD’s automated operations are supported by “thousands of COBOL scripts computing millions of transactions,” the strike team report states. Yet there are “60 full-time employees” dedicated to managing the mainframe operations of EDD.

“Nobody’s really improved on it. It’s a wonderful software system, but it’s not interoperable,” said Jane Oates, president of the nonprofit WorkingNation and a former assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of Labor. So you’ll hear things in California like people have to call in and their call gets dropped.”

People who are skilled COBOL coders are “really smart people who know how to rework and, and kind of MacGyver the system,” Oates said. However, she added that “they’re fixing things with chewing gum and dental floss.”

“ ‘All of those things are happening in other places as well, but nowhere is the system as pushed as and strained as it is in California’ ”

That might explain why a Bay Area resident, who didn’t want her name used, said her benefits were unexpectedly and inexplicably paused for six weeks after she had been receiving them for months. She could never reach anyone by phone even though she would start right when the EDD supposedly opened. Another Bay Area woman said that during her nearly four-month ordeal with the EDD, the only human she was able to reach was in the IT department.

“All of those things are happening in other places as well, but nowhere is the system as pushed as and strained as it is in California,” Oates told MarketWatch.

Over time, many states have shifted away from COBOL to cloud computing as workers who are fluent in the programming language increasingly retire, Michele Evermore, a senior policy analyst at the National Employment Law Project, an advocacy organization focused on workers’ rights, told MarketWatch.

“The problem is that unemployment insurance is inherently a crisis program. During good times you can have this dodgy computer system and manually shove people through, but when you have to do a lot of changes quickly it’s not the right system,” she said.

“The big challenge with COBOL mainframes is not that they don’t work. They’re very reliable, they don’t crash, and they get done what they need to get done. But what you can’t get out of them is reports,” Jensen said.

“So if you want to understand how data is flowing through your system, you have to literally code individual reports,” said Rhode Island’s Labor Department director Scott Jensen. Without doing so, it would be virtually impossible to figure out what commonalities there are in jobless applications that are being held up, he said.

Rhode Island began the process of shifting most of its operations to Amazon Web Services AMZN, -1.97% cloud computing software, realizing early on that their systems which were coded in COBOL would not be able to handle the predicted influx of jobless applications.

“We had an analog phone certification system that could take 5,000 calls at a time,” he said. According to the projected number of claims his team calculated they would be receiving, “we were going to get 250,000 calls a day.”

“It doesn’t take a genius to understand that you’re going to get completely swamped by that,” Jensen, who previously served as deputy secretary of the Maryland Department of Labor, said.

Eventually, “the whole consumer interface will be completely cloud-based, which allows you to do things that nobody’s ever done in unemployment insurance,” Jensen said of Rhode Island’s modernization project.

His team refers to the interface as a “pizza tracker” because users will be able to follow their claims “the way that you follow your Domino’s Pizza order.”

“You can be rest assured that your pizza is coming.”

“This is where it is, the drivers got lost, but she found her way, and it’s gonna be there in a little while,” he said metaphorically referring to checking the status of your unemployment claim. That effectively keeps people from calling the call center, which is crucial “because you cannot possibly staff up enough to deal with the volume of calls.”

Throughout the pandemic, Rhode Island’s backlog of claims has almost never exceeded 14 days, he said.

“But if you looked on our Twitter account, and you look at our call center, we were getting inundated with people who were saying ‘I messed up my PIN number and I can’t get into my account,’ or ‘I need to change my bank’.”

“While we were doing great on the backlog of new claims, we were serving people poorly, who had to keep their claims going.”

Jensen assigned more employees to the call center. But — unlike earlier in the pandemic when Amazon Web Services wasn’t being used — his team received detailed data reports on which phone numbers were generating the majority of the calls.

It turned out that 1,000 people generated nearly 10,000 calls a day to the call center. Some did so by “hiring robocall services to call the call center on their behalf.”

And today? Access to the reports AWS generated allows his team to set more realistic goals and staffing according to the number of actual people calling as opposed to robocallers.

EDD is on track to “implement a long-term fix to the patchwork system that utilizes COBOL programming,” Levy said.

How you can expedite your claim

There’s no magic fix to getting your claim prioritized or even reviewed in the first place in California or other states with a backlog, but experts MarketWatch spoke with identified some techniques that could help.

Be extremely careful when filling out your application, Oates recommended. “Because any mistake, even putting in a comma instead of a period, spits out your application.”

She also recommends joining Facebook FB, -0.29% unemployment-advice groups or contacting community organizations such as Goodwill. “They could tell you things that were successful for other people in the same situation.”

“People need to remember that unemployment insurance is an insurance program, which means you only insure something that’s valuable. It is not something that anyone should feel bad about having to rely on,” Jensen said. “If you’re not taking the service that you need, I think that you should bother as many politicians as you can.”

“We have had to respond to a lot of political pressure, and that was a good thing,” Jensen added. And if you are able to speak with someone from your state’s labor department? “Remember that the person you’re speaking with has been doing that all day long, and they really do want to help you.”

“They understand that you’re frustrated, but just try to get down to business as fast as you can. Have all the paperwork you can possibly think of in front of you so that you can really make the use of that time because it is a piece of temple real estate.”