This post was originally published on this site

The coastal town of North Wildwood, N.J. experienced this flooding from a mix of high tide and a winter storm in 2016.

Getty Images

As if municipalities and muni-bond investors don’t have enough to worry about with a recession and dropping tax revenue because of the coronavirus, a recent report from Moody’s Investor Service suggests coastal state and local governments face increased credit risks from rising sea levels as more frequent and severe flooding threaten coastal communities’ economies, property values and critical infrastructure.

These increased credit risks could hurt municipalities from smaller towns economically dependent on fishing and shipping to even rich beach towns looking to borrow in the $3.85 trillion muni bond market to pay for everything from road repaving to a seawall.

To be sure, insurers and other credit-ratings firms have pointed out climate-change risks for municipalities before, but that was before COVID-19 weakened their finances. States and local governments have seen tax revenues drop and expenses rise because of the coronavirus pandemic. Some states, such as New Jersey, were already in bad shape financially because of unfunded pension liabilities.

It’s going to take a few years for municipalities to realize the full impact of the coronavirus on their economies. For towns reliant on industries hit hard by the pandemic, their revenue streams could fundamentally change. That makes embarking on a pricey infrastructure project to address storm surges hard to fathom now. But coastal communities do so at their peril. Already, the Atlantic and Gulf coasts have seen a 100% to 150% increase in annual flood days since 2000, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The pandemic “will be worked out over time, but climate change will continue,” says Leonard Jones, managing director, public finance, at Moody’s, who contributed to the report.

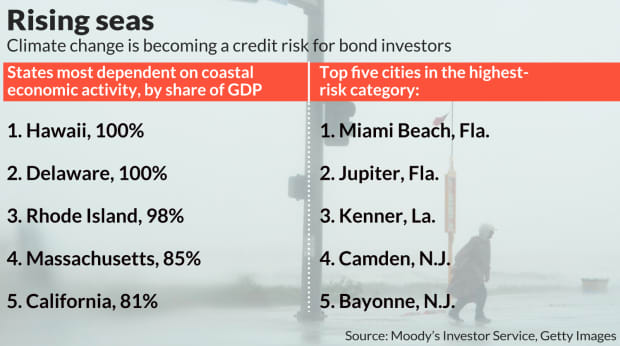

Moody’s and its climate data affiliate, Four Twenty Seven, estimate that in 20 years rising sea levels and flooding will impact every coastal state, most of their coastal counties, and over 110 cities with a population greater than 50,000 that are most at flood risk.

Who’s most at risk?

The report flagged three states — Florida, New Jersey and Virginia — at high economic and credit risk because the towns and regions that generate a significant portion of overall state and individual county economic activity. These areas are in a 100-year flood zone, and the report states towns in these areas have a 26% chance of flooding over the next 30 years.

Moody’s said several of Florida’s economic powerhouse counties have the majority of their business are in the 100-year flood zone, such as Miami-Dade County (rated Aa2 with a stable outlook), at 47%; and Broward County (Aaa, stable) at 30%. Already, some buyers may be shying away from that Florida vacation condo because of climate risk

Beach towns aren’t the only ones at risk. Norfolk, Virginia (Aa2, stable) has 20% of its economic activity in the flood zone. Other non-beach towns also at risk include Camden, N.J., opposite Philadelphia, and Kenner, Louisiana, on Lake Pontchatrain and home of the New Orleans airport.

“They (Moody’s) really are putting all of these coastal municipalities on notice. And it’s not just the municipalities. Importantly, they’re putting the states on notice,” says Mayra Rodriguez Valladares, managing principal of MRV Associates, a bank and capital markets consulting firm.

“ State and local governments’ ability to manage debt levels while investing in adaptation efforts will become increasingly crucial to credit quality. ”

States with large coastal populations and economies face credit risks over a multi-decade horizon because of a weaker economy, increased maintenance costs and lost tax revenue, the report states. That’s going to be particularly hard on financially stressed states like New Jersey, Valladares says.

Lyle J. Fitterer, senior portfolio manager at the $1.3 billion Baird Short-Term Municipal Bond Fund BTMIX, , says financial stress on cities could increase, even those with good credit rates now, especially as Covid-19 hits revenue.

“If (a city) gets downgraded because of COVID and they happen to be a coastal community that also has the threat of rising sea levels, those things can start to compound over time. We would assign more risk to that just because their overall financial picture has changed,” he says.

Other states in better fiscal shape have their own risks. For example, 32% of Texas’ GDP is tied to the coast; however, Harris County (Aaa, stable), which includes Houston, contributes 26% of the state’s GDP and has 16% of the county’s GDP is generated in the 100-year flood zone.

Blake Cullimore, associate vice president and analyst at Moody’s Investor Service, and the report’s lead analyst, says the authors tried to put in context how they approach municipal credit ratings to account for sea level rises and the risks relative to the local economy and debt leveraging.

State and local governments’ ability to manage debt levels while investing in adaptation efforts will become increasingly crucial to credit quality, the report says.

Fitterer says governance issues have always been important in the muni-bond market, but the coronavirus and climate-change risks heighten environmental, social and governance issues. Fitterer says Baird is trying to build in climate risks like sea-level rises into their analysis. Decisions still comes down to creditworthiness, and if a poorly rated municipality in a coastal area issues a bond, “we need to get paid more for a weaker credit in an area like this, relative to a weaker credit in an area not like this,” he says.

Wealthier regions with well-rounded economies generally have higher credit ratings. However, richer, high-population areas prone to flooding could see “climate migration” from wealthy flood-prone areas to low-wealth areas less prone to flooding, the report says.

That may impede their ability to finance projects to combat rising sea levels, which could ultimately lead to higher financing costs, Fitterer says.

Valladares and Fitterer agree with Moody’s that federal and state governments will need to help local governments shore up their coastal areas, but the report says all Gulf states, particularly Alabama, lag other areas when it comes to state-level policies to combat sea-level rises and storm surge. That leaves coastal cities on their own, vulnerable to flood damage and putting their credit quality at risk.

Even though communities may be struggling with competing demands for financing, the current low interest rates make it a good time for some municipalities to issue green bonds or other notes earmarked for these infrastructure projects, Valladares suggests, especially as some investors are willing to take risks for higher yield. “I think that there’s a lot more consciousness now,” she says.

Kevin DeGood, director of infrastructure policy at the Center for American Progress, says environmental risks may be a low priority for local governments now as they grapple with other, more immediate challenges. That may change if bond underwriters start asking about climate risks. “If the traditional pool of investors all of a sudden feels a little skittish, that’s the event that triggers the conversation,” he says.

Now read: Half of the world’s beaches could be wiped out by the end of the century

And: After underperforming the stock market for years, alternative energy is red hot

Debbie Carlson is a MarketWatch columnist. Follow her on Twitter @DebbieCarlson1 .