This post was originally published on this site

Women ages 25-44 are more than three times as likely as men not be working due to childcare demands during the pandemic, according to a report by the Federal Reserve and U.S. Census Bureau (Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

Getty Images

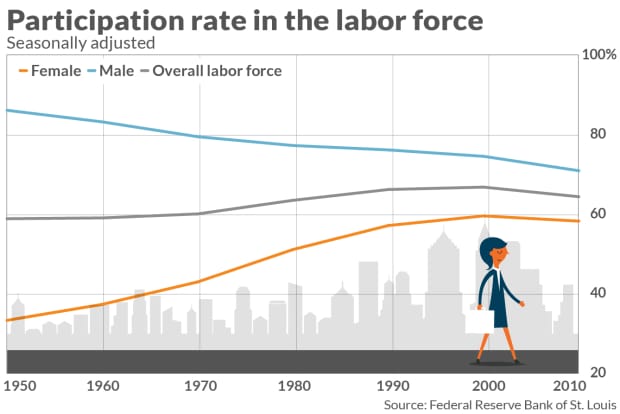

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, the introduction of birth control, paid family leave, anti-sexual harassment laws and rising wages were just some of the factors that drove masses of American women to enter the workforce in the 1970s.

More women continued to enter the workforce through the late 1990s, though at a much slower rate than in prior decades. Still, American women came a long way from the early 1950s, when they made up roughly 30% of the workforce, to the late 1990s when they made up 60% of it.

But the pandemic is starting to undo decades of progress as record amounts of women leave the workforce.

In February, the labor force participation rate for women, a measure of the share of women working or looking for a job, was 57.8%. By April, that rate declined to 54.7%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ data.

Rates increased in June to 56.1%, but by September they fell to 55.6%, the lowest reading since 1987 apart from April and May, the New York Times reported.

“It’s upsetting to see these changes happen so fast over the past six months,” said Kate Bahn, director of labor market policy and economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, a nonprofit research and grant-making group.

In prior recessions, parents with school-aged children, in particular, who were laid off from their jobs could apply and interview for a new position while their child attended school or daycare.

But not in the age of coronavirus.

“Child care needs and the uncertainty about the future of the American economy are making it hard to even begin the process of searching for a new job,” Bahn told MarketWatch.

The child care dilemma

Many schools across the country have started off the school year with virtual instruction, which for many parents means essentially home-schooling their children.

One in five working adults said the reason they stopped working “was because COVID-19 disrupted their childcare arrangements,” according to an August report published by the Census Bureau and the Federal Reserve.

“Of those not working, women ages 25-44 are almost three times as likely as men to not be working due to childcare demands,” the report states.

As a result, many jobless parents have put off applying for work altogether.

Last month, a total of 4.5 million Americans reported that they had not looked for work in the last four weeks, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Women are the majority of these workers.

“ ‘Of those not working, women ages 25-44 are almost three times as likely as men to not be working due to childcare demands’ ”

By definition, these workers are not considered unemployed because they did not actively look for work in the past four weeks and therefore are not factored into the unemployment rate. However, they may still qualify for unemployment benefits due to provisions in the CARES Act.

Among prime-age workers (people between ages 25 to 54) women account for 63% of unemployed people in the U.S. who did not actively look for work during the last four weeks.

“Historically, women have largely been responsible for child care and tend to earn lower wages than men,” said Stephanie Aaronson, a former Fed researcher who is now at the Brookings Institution, a left-leaning think tank based in Washington, D.C.

For those reasons, in opposite-sex relationships, women are more likely to drop out of the workforce, she added.

When women drop out of the workforce, it’s not just their families that are put at a disadvantage, but the overall U.S. economy, Nicole Mason, president of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, which advocates for more women’s rights at home and in workplaces.

“Women make up more than half the workforce. If they stop working, that’s income and earnings that don’t get pumped back into the economy,” Mason said.

“The economy grows faster when more women participate in the workforce,” Aaronson said. “Our potential output is higher, and we can more easily support the government through income taxes and raise more money to fund Social Security.”

“ ‘Women make up more than half the workforce. If they stop working, that’s income and earnings that don’t get pumped back into the economy’ ”

That, among other reasons, is why it’s so important that women return to the workforce. But it will likely require significant structural changes to bring women back into the workforce.

More affordable and accessible child care will be key to bringing women back into the workforce, experts say

Even before the pandemic the cost of child care, both center-based and home-based, were consistently rising year over year.

Now parents could be looking at even higher costs of child care.

Some 35% of child-care centers and 21% of family child-care programs in the country remained closed as of July even after some restrictions were lifted, a report published by the nonprofit Child Care Aware of America, which advocates for access to affordable child care, found.

Centers that remain open could become more costly due to factors such as reduced capacity necessitated by physical distancing, supplies including personal protective equipment, training on new safety measures and communication of protocols to employees and parents.

In European Union countries, child care and paid family leave are both treated as public goods, meaning they are funded through taxes. That’s made it possible for a greater share of women to participate in the workforce, Aaronson said.

But more European women tend to work part-time and “don’t progress as much in their careers,” she added. “In the U.S., there are more women in management positions who tend to work full-time.”

In the U.S., child care is means-tested, meaning that lower-income families receive higher subsidies to cover the cost of child care.

That said, families making under $1,500 a month shelled out nearly 40% of their income to child-care. “We as a country should think that’s unacceptable,” Mason said.

“Child care needs to be accessible, cost-effective and high quality for families across all income levels,” she said. Mason said she’s in favor of making child care a public good so that fewer families have to question whether their child is safe and if they can afford to work because of the cost of child care.

Job training

In addition to the child care dilemma women are facing, jobs within the child care and education sector, which women disproportionately hold compared to men, have also vanished during the pandemic.

Many of the industries that have been hit hardest by the pandemic — leisure and hospitality, government, food services and retail — also disproportionately employed women.

“ ‘It’s clear some companies are planning for a future where with or without a vaccine people travel less. It will be much more difficult for women to reenter the workforce if their jobs disappeared.’ ”

Some of those industries could bounce back once a vaccine is available and widely distributed, and once schools reopen for in-person instruction “some women will start trickling back into the workforce,” Aaronson said.

However, “the economy is currently undergoing structural changes,” which could leave many women permanently unemployed.

“It’s clear some companies are planning for a future where with or without a vaccine, people travel less. It will be much more difficult for women to reenter the workforce if their jobs disappeared. We need programs to help both women and men adjust to a new landscape.”

It’s particularly important that both men and women partake in the same programs so that women aren’t “mommy-tracked”. Meaning that once the economy springs back from the coronavirus induced-recession, in the next inevitable recession women won’t necessarily be more vulnerable than men in terms of job security.

There’s a huge role for community college and vocational schools to play in this next chapter to help figure out the best industries to pivot to next and gain the necessary skills to work in them, Aaronson said.