This post was originally published on this site

Palantir’s business has grown since its launched Foundry, its corporate platform, in 2016.

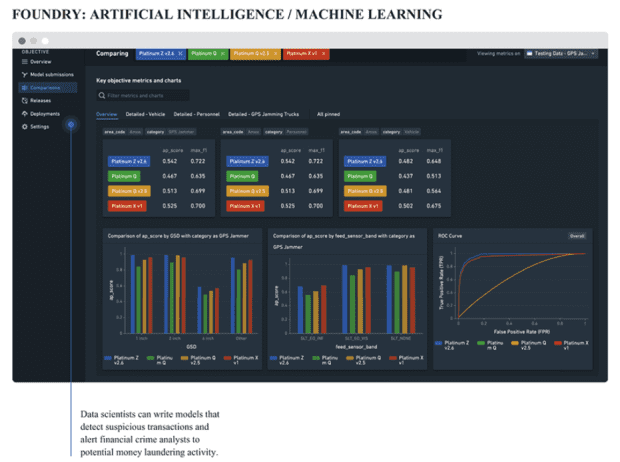

Image from Palantir’s S-1 filing

Palantir Technologies Inc. was known for years as being the most secretive unicorn startup in Silicon Valley, but going public has turned the company from a shrinking violet to an exploding fountain of information.

Palantir publicly filed for a direct listing on Aug. 25, and plenty has happened in the month since.

- In its original filing, Palantir Chief Executive Alexander Karp loudly and publicly broke up with Silicon Valley in a letter at the very beginning of the document, a unique approach that sought to defend Palantir’s secretive work building surveillance and warfare capabilities for the U.S. government and allies. The letter confirmed earlier reports that Palantir had moved its headquarters from Palo Alto, Calif., to Denver, and seemed to denigrate advertising-based businesses such as Facebook Inc. FB, +0.78%, for which co-founder Peter Thiel serves as a board member. “Our company was founded in Silicon Valley,” Karp wrote. “But we seem to share fewer and fewer of the technology sector’s values and commitments.”

- The company then revised its public filing six times; along with early versions submitted privately to the Securities and Exchange Commission, Palantir is now on the 11th version of its offering filing. It even revised its filing twice in one day and reversed changes that a TechCrunch reporter detailed on its voting structure. Palantir made that move after warning investors in its filings about getting information from the media.

- Executives held a public webcast in which they discussed the company and its financial performance for two full hours, which again led off with a unique personal message from Karp, who was filmed while cross-country skiing. Executives then spent a half hour taking questions from potential investors, with both those videos posted online for later consumption.

- Palantir later issued forecasts for the rest of this year and for 2021, which companies cannot officially do for an initial public offering but is allowed for a direct listing.

- Meanwhile, protesters have demonstrated at the company’s old headquarters in Palo Alto, its new headquarters in Denver and its office in New York, mostly focusing on the company’s work with the Immigration and Customs Enforcement division of the U.S. government.

After all of that, The Wall Street Journal reported Sept. 24 that Palantir had informed investors that shares were expected to begin trading around $10 apiece, a price that would give the company a valuation of roughly $22 billion. Shares are expected to begin trading Sept. 30 on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol PLTR.

Here is what you need to know about Palantir’s direct listing.

Big-data software that got its start with the CIA

The core reason Palantir has been both secretive and controversial since its founding in 2003 is that it began with money from the Central Intelligence Agency to develop data-crunching software for the government. Palantir received original funding from In-Q-Tel, the CIA-funded nonprofit venture-capital arm, to develop its first major product, Gotham, which launched in 2008 to help government entities with surveillance and warfare planning, among other uses.

“Defense agencies in the United States then began using Gotham to investigate potential threats and to help protect soldiers from improvised explosive devices,” Palantir disclosed. “Today, the platform is widely used by government agencies in the United States and its allies.”

Palantir has moved beyond that business, however, and started serving corporate clients in 2016 with its second platform, Foundry. Palantir now says that a little more than half — 53% — of its customers come from the private sector instead of government, even as Palantir considers different divisions in the same government departments as separate customers.

While the majority of Palantir customers may be commercial businesses, that doesn’t mean the majority of its revenue comes from those contracts. Palantir had only 125 customers in the first half of this year that paid an average of $5.6 million each in 2019, but the top 20 customers spent an average of $24.8 million in spending in 2019. And its three largest customers — which Palantir does not name — account for up to a third of the company’s revenue and on average have been customers since well before Foundry was launched.

“Our top three customers together accounted for 33% and 28% of our revenue for the years ended December 31, 2018 and 2019, respectively, and 31% and 29% of our revenue for the six months ended June 30, 2019 and 2020, respectively,” the company disclosed. “Our top three customers by revenue, for the year ended December 31, 2019, have been with us for an average of 8 years as of December 31, 2019.”

Palantir said it had contracts with government entities for an additional $1.2 billion in business on its books, and an additional $2.6 billion in “indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity” contracts that are not counted because the funding has not yet been determined.

“Palantir is best known for its work with the U.S. government,” MKM Partners executive director Rohit Kulkarni wrote recently in an examination of Palantir. “This includes a contract with the Army to develop a new intelligence interpretation platform, worth an estimated $823mn. Palantir also worked with U.S. Customs and Border Protection to track immigrants at the border, and in 2018, was found to be secretly testing its predictive policing software in New Orleans.”

Growing revenue and growing losses

Palantir revealed in its SEC filings that revenue grew to $742.6 million in 2019 from $595.4 million in 2018, while losses stayed even at more than half a billion dollars a year — $579.6 million in 2019 and $580 million in 2018. In the first six months of this year, Palantir recorded a loss of $164.7 million on revenue of $481.2 million, after recording a loss of $280.5 million on sales of $322.7 million in the same period of 2019.

In their presentation to investors, Palantir executives stressed the revenue growth that it has experienced since moving into the commercial sector with Foundry.

“We did $743 million in revenue last year, but I’d like to go back to 2017, when we did just over $500 million in revenue and only grew at a rate of 11%. Nothing exceptional about that,” Kevin Kawasaki, Palantir’s head of business development, told investors. “What is exceptional is that we’ve accelerated the growth in revenue every year since. In 2020, we’ve grown 49% through the first half of the year and we’ve also grown our gross margins to 78%. So we’re growing 49% on an extremely large base with 78% gross margins. We don’t see anyone else doing this.”

The company predicts it will continue to post strong revenue growth in the coming months, though the percentage gain will decline. In its forecast, Palantir calls for revenue growth of 46% to 47% in the third quarter, 41% to 43% for the full year of 2020, and greater than 30% in 2021.

Even with that forecast, Kulkarni was not impressed with what he termed “very limited disclosure” from Palantir, especially when compared to information disclosed by other software-as-a-service, or SaaS, companies going public of late.

“Despite having a 15+ years operating history, we found Palantir’s S-1 filing fairly light on customer trends, SaaS metrics. Also, the company has disclosed only six trailing quarters worth of financials,” Kulkarni wrote.

Even without an IPO, plenty of shares exist

Palantir decided to go with a direct listing instead of an IPO, following other mature startups such as Slack Technologies Inc. WORK, -0.66%, Spotify Inc. SPOT, +0.18% and Asana Inc., which is expected to begin trading this week.

For more: 5 things to know about the Asana direct listing

The most prominent way a direct listing differs from an IPO is that the company does not create nor sell any new shares. For Palantir, though, years of venture-capital investments have created more than enough shares to launch public trading: roughly 1.64 billion, though that grows to 2.17 billion in a fully diluted formula that includes vesting options.

Not all those shares will trade openly at the launch, though. Most of the shares are locked up through the end of the year, a common practice for IPOs but unusual for a direct listing. Palantir said in a news release Friday that it expects a total of 461.2 million shares will be permitted to be sold on the first day of trading, though there are no guarantees that all of those shares will hit the market.

The rest of the Palantir shares will largely become available to sell on the third trading day after Palantir publicly announces its 2020 earnings, which would be expected early next year. In the meantime, strong demand for the limited number of shares could drive prices higher, as they have for recent hot software IPOs like Snowflake Inc. SNOW, +9.34% and Unity Software Inc. U, +6.62%

For more: Software companies IPO like its 1999

Direct listings typically seek a “reference price,” largely based off of previous sales of the company’s stock on the private market. The Journal’s report of an expected $10-a-share price for Palantir stock jibes with recent prices for its shares in private markets: While the volume-weighted average price of shares from January to September was $6.02, that price in August was $7.31, and the average on Sept. 1 was $9.17 before Palantir halted private transfers of its shares in preparation for the direct listing.

There is no guarantee that will be the starting price for Palantir, however. Palantir listed a dozen banks that are acting as financial advisers on the deal, with Morgan Stanley as the main consultant with the designated market maker, which will determine the opening price of the shares.

So, about that share structure and voting power…

While Palantir has publicly split with Silicon Valley both physically and metaphorically, it is taking with it the Valley’s approach to stock structure — giving founders extra votes to maintain control of the company after it goes public — and super-sizing it.

The typical approach for companies seeking to ensure their founders retain control after a move to the public markets is to create two classes of shares, and give the class of shares held by founders and important insiders extra votes. This approach is why Mark Zuckerberg rules over Facebook like a king and Google’s co-founders retain control over the company even after they walked away from day-to-day management.

From 2017: Founder-friendly share structures are here to stay

Snap Inc. SNAP, +4.25% seemed to take this to an extreme by offering no votes to common holders of the stock, but Palantir is taking it even farther. The company has established four different tiers of stock, three of which are familiar: Class A stock with 1 vote, class B stock with 10 votes, and preferred shares for certain investors that are not typically counted in the same way as other classes of stock.

Palantir added another class of stock, though, deemed class F for the founders. And the company says the voting rights of those shares of stock can vary, basically meaning the founders can have control whenever they want.

This class of stock has caused much of the confusion around the offering and been the focus of many of the revised versions of Palantir’s SEC filing. TechCrunch’s Danny Crichton has tracked the changing language that Palantir has been adding to try to make sense of the unique stock structure, and it was his reporting on the fifth revision of the S-1 that seemingly caused Palantir to issue a sixth revision striking the language that he highlighted.

Much of the language that was stricken dealt with the variable nature of the shares, including a statement that the founders would unilaterally be able to adjust their voting power. But the underlying nature of the stock remains: The amount of power they hold can be changed, giving the founders control of the company when they see fit. Of course, how that works is still mighty confusing, as you can see in this chart that is the clearest and most prominent explanation of how the class F shares would work in practice, appearing on page 10 of the 300-plus page filing.

OK, so who are these founders?

Karp, Thiel and Stephen Cohen make up half of Palantir’s six-person board, own all of the class F shares, and sit in the three most powerful seats in the company — CEO, chairman and president, respectively. Yet Palantir’s filing offers little information about the trio beyond the heavily updated legalese involving their voting power.

Palantir actually has its roots at PayPal Holdings Inc. PYPL, +2.54%, though you wouldn’t know that from the filing, which mentions PayPal only once in describing Thiel as a co-founder. The generally accepted story of Palantir’s founding involves Thiel attempting to take the approach PayPal used to detect and block fraud on its platform and transfer it to antiterrorism efforts for a post-9/11 America. He pulled together some Stanford University students, including Cohen, to start developing the software, then put his former Stanford roommate, Karp, in charge of the company.

Thiel has grown in prominence since then, as he became Facebook’s first outside investor around the same time he was co-founding Palantir and soon launched the Founders Fund to invest in other companies. Additionally, he was one of the few prominent tech names to support Donald Trump’s bid for the presidency, even speaking at the Republican National Convention in 2016, and he reportedly funded a legal attack that eventually took down the news website Gawker.

Karp, whom the Journal called “a self-described socialist” in a 2018 profile, did not have much work history to speak of before Thiel installed him as CEO of Palantir; he had just finished his PhD in philosophy in Germany when he returned to the U.S. and took the job. His description in the filing cites only his educational background and years with Palantir, and the same is true of Cohen, who does not have much of a history beyond the company and his education.