This post was originally published on this site

Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

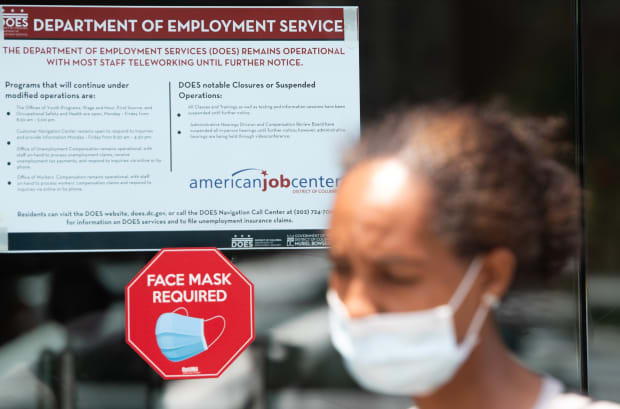

The nation’s unemployment insurance system is broken. It pays the unemployed too little, and too few workers are covered by the states’ various programs.

The system is a complex federal-state partnership. States levy payroll taxes and establish benefit levels but they may borrow from the federal government if their trust funds run low.

Displaced workers are paid a percentage of lost wages up to a cap.

Prior to COVID-19, the nationwide average benefit and wage of insured workers were $378 and $1,126 per week—a 34% wage replacement. In Hawaii, the figure is 54% but only 26% in Washington, DC.

In most places, 26 weeks of benefits is the norm, but Florida and North Carolina only provide 12 weeks. The CARES Act temporarily extends benefits an additional 13 weeks.

Many aren’t eligible

Part-time employees, gig workers, freelancers and those who quit or are fired for cause are ineligible. The national average eligibility rate among the unemployed prior to the crisis was only 29%—in Mississippi it was 9.5% and in Massachusetts 58%.

During crises, layoffs are visited more frequently on full-time eligible workers, but state benefits still don’t cover the majority of the unemployed. In May, 10.7 million claimed emergency CARES Act federal assistance who would have not received state benefits.

Low income and minority workers are more concentrated in temporary employment. During the Great Recession, workers with incomes below the 30th percentile were half as likely to receive benefits as those above that threshold.

Quite simply, the unemployment insurance system is inadequate to maintain—especially the working poor who live at the edge. And no one should be surprised to see middle-class Americans queuing at food banks.

The $600 federal supplemental benefits under the CARES Act ended July 31—consequently, the recovery is slowing. The economy and employment will be substantially smaller next February than had the pandemic not occurred.

Federal issue

Looking at benefit levels, unemployment insurance is not a priority for middle-class swing voters. They must rely on savings, or aid from domestic partners or extended families, and unemployment insurance is seldom a campaign issue.

States compete for employers. Keeping eligibility criteria tight and benefits and payroll taxes low helps attract businesses sensitive to overall labor costs.

In this century, recessions are less frequent than during the post-World War II decades but when they arrive, they are terribly more severe. State unemployment insurance systems and national efforts to boost household income and spending have become reliant on federal emergency legislation to boost state benefits and broaden eligibility.

That worked reasonably well in the wake of the Financial Crisis but not this time. CARES Act provided an additional $600 a week—absurdly raising combined state and federal payments to above prior earnings for about 68% of the unemployed—and broadened eligibility to cover many gig and self-employed workers.

Other than extending state benefits an additional 13 weeks, those supplemental benefits have mostly run out, and the Republicans and Democrats in Congress can’t seem to come to a compromise about an appropriate benefit level going forward.

The president has authorized another $300 per week from emergency funds. Forty states have been approved but most have not yet processed those funds and he only has enough money to last about six weeks.

A recent academic study showed CARES Act benefits did not discourage workers from returning to old jobs. That’s not surprising, because temporary jolts of extra income and crises encourage households to pay down debt and supplement savings but do not much affect long-term decisions such as taking a job.

Delay needed adjustments

Establishing an excessively large federal supplement for a duration of 12 months or until unemployment falls below a certain threshold could encourage workers to stay at home and collect the benefits. It would certainly postpone workers reckoning with the need to retrain or relocate as it becomes apparent many jobs are permanently lost.

The program should be federalized to provide adequate benefits during a crisis. A reasonable plan would provide 75% income replacement up to the average weekly wage with standardized eligibility requirements. Folks who earn more than the average wage could be encouraged to establish unemployment tax-sheltered savings accounts similar to IRAs, and benefits could be extended to 52 weeks when unemployment is above 7%.

Peter Morici is an economist and emeritus business professor at the University of Maryland, and a national columnist.

More from Peter Morici:

Ballooning federal deficits threaten Fed independence, and give an opening to Chinese yuan