This post was originally published on this site

US dollar bills.

Getty Images

Jason Brady, CEO of Thornburg Investment Management, knows that sitting on the sidelines can be unpopular.

“Cash is very much maligned in the context of providing yield. It costs money to hold cash. I understand people’s reluctance,” Brady said, adding that’s also one reason why the Federal Reserve “makes cash earn zero, is so that people don’t own it.”

Even so, Brady thinks the time is ripe to put more cash on the sidelines as volatility in the U.S. stockmarket picks up, as Congress drags its feet on providing additional fiscal stimulus, and as rancor in Washington intensifies ahead of the Nov. 3. elections.

“You can turn cash into anything,” he told MarketWatch. “But you can’t turn anything into cash.”

Brady oversees strategy and direction for the Santa Fe, N.M.-based Thornburg and its roughly $41 billion worth of client assets. He’s also a co-manager of the multi-asset Thornburg Investment Income Builder Fund TIBIX, +0.10%, the fixed-income Thornburg Limited Term Income Fund THIIX, -0.07% and Thornburg Strategic Income Fund strategies TSIIX, -0.08%.

Several of the firm’s bond and opportunistic fixed-income strategies are holding 10% cash, he said. Another fund manager said more than 3% to 4% cash for a bond or strategic-income portfolio could be considered a lot.

“We are holding more cash, even though the Fed is telling us not to,” said Brady, who after business school worked for a year as a corporate bond trader at Lehman Brothers and then for Fidelity Investments and Fortis Investments.

A key concern has been how little investors have been getting paid during the pandemic to invest in U.S. high-yield or “junk-rated” companies.

“Credit spreads are really tight and we’re in a recession,” he said, pointing to the level of compensation investors earn on certain bonds above U.S. Treasurys TMUBMUSD10Y, 0.657% or other risk-free benchmarks.

Another worry has been how little creditors have been recovering on defaulted debt amid a deluge of new bankruptcies in 2020.

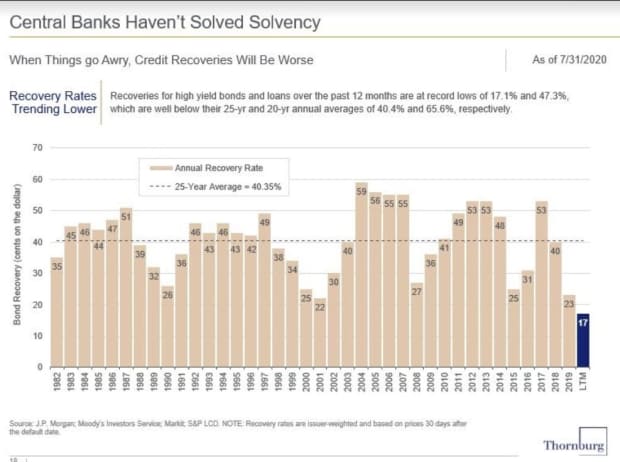

This chart shows a recovery rate of about 17 cents on the dollar on defaulted U.S. high-yield bonds and loans over the last 12 months, a record low.

Dimes on the dollar

That’s down from a 20-year annual average of 65.6%.

The Federal Reserve has been working to keep credit flowing during the pandemic, including by promising to hold interest rates near zero until well after the economy has recovered from the COVID-19 crisis, and by making history with its first foray into buying corporate debt.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s mantra has been that its aid and bond-buying program will remain nimble and adjust to market needs, meaning it can quickly ramp up or slow down its asset purchases.

Yet, the Fed can do only so much without Congress holding up its end of the bargain when it comes to supporting U.S. households, businesses and cities during the COVID-19 crisis which rattled markets this week with cases rising worldwide and new calls for business shutdown measures.

To restart stalled talks in Washington on a new fiscal stimulus bill, House Democrats on Thursday laid out plans to work on a $2 trillion-plus plan, which would include unemployment add-ons, checks to households, a revival of the Paycheck Protection Program for small businesses and aid for airlines and restaurants.

But the clock is ticking before Capital Hill empties out next week and attentions turn to election campaigns. Against that backdrop, Brady’s cash could be getting more company on the bench.

Some $26.9 billion fled U.S. stock funds in the week ending Sept. 23, the biggest weekly outflow in nearly two years.

A late-session rally Friday that capped off a choppy week, led major U.S. stock indexes to close higher, but for the week, the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, +1.33% finished 1.8% lower, the S&P 500 index SPX, +1.59% off 0.6% and the Nasdaq Composite Index COMP, +2.26% up 1.1%.

The market for riskier U.S. corporate debt also went into retreat. The week saw $4.9 billion yanked from U.S. high-yield exchange-traded funds (ETFs), the sector’s worst weekly outflows since March, according to BofA Global.

Outflows for the sector’s two-biggest ETFs accounted for nearly all of it, namely, the iShares iBoxx $ High Yield Corporate Bond ETF HYG, -0.18% and SPDR Bloomberg Barclays High Yield Bond ETF JNK, -0.09%.

“The market weakened meaningfully this week, as the gravity of overextended levels, calendar indigestion, equity volatility, and election uncertainty weighed on risk appetite,” wrote Oleg Melentyev’s credit team at BofA Global Research in a note Friday.

“The index is now 60bps off its recent tights and only a few basis points inside of our spread target of 550bps.”

Related: Junk bond jitters may signal the start of a stock market capitulation