This post was originally published on this site

Auto workers protest the closing of GM’s Lordstown (Ohio) plant in March 2019.

Getty Images

Donald Trump came to power promising to fix a trade system that has hurt U.S. workers and businesses for generations. He railed against trade deals, raised alarm about the trade deficit, and promised to bring back jobs. “You won’t lose one plant, I promise you that,” he told Michigan voters in 2016.

Four years later, Michigan has actually lost three major auto plants.

Even before the pandemic, the state’s job growth had plunged to its lowest level in a decade, my co-authors and I found in a new report, with investment from the auto industry down 29%. Next door in Ohio, annual job creation also collapsed—from 36,200 in 2016 to just 3,700 in 2019. And the U.S. trade deficit has been higher every single year of Trump’s presidency than it was when he took office.

“ American farmers have lost an important market—in some cases their most important market—and American taxpayers have borne the cost, as Trump has had to replace farm income with billions in compensation checks from the government. ”

The truth is, Trump failed these workers. With Trump and Joe Biden set to face off on a debate stage in Ohio on Sept. 29, it’s a good time to ask: What are the real problems with U.S. trade policy, and what would a better approach be?

U.S. trade problems were a long time in the making.

The process through which U.S. trade policy is made has long been vulnerable to special and corporate interests.

U.S. trade policy is carried out by the U.S. Trade Representative, the negotiating arm of the executive branch, based on broad instructions from Congress and informed by a system of “advisory committees.” In theory, these committees should bring a wide array of voices and interests to inform the executive branch negotiators.

Instead, they’ve become a club for corporate interests. A 2014 Washington Post review found that all but two of the 19 sectoral advisory committees exclusively contained representatives of private firms and their business associations. In the remaining two—for agricultural trade and animal products—those interests made up 90% of the members.

Under Trump, the corporate domination of trade policy has gotten worse.

Opinion: A Nobel laureate makes the economic case for Joe Biden

“ As a result of this corporate domination, trade policy over the last few decades has been tailored to help corporations maximize their profits, not to help American workers or small businesses. ”

The overall advisory committee, the Advisory Committee for Trade Policy and Negotiations (ACTPN), had 19 industry representatives and 12 public advocacy representatives (from unions, think tanks, state government, and an environmental group) under Obama. Under Trump, it still has 19 industry representatives—but the number of non-industry representatives has dwindled to just three, including a Republican governor and the president of a conservative think tank.

As a result of this corporate domination, trade policy over the last few decades has been tailored to help corporations maximize their profits, not to help American workers or small businesses. Outsourcing has become easier, which pushes down U.S. manufacturing wages and investment.

Trump’s approach has made these problems worse.

As a candidate, Trump promised to reverse these trends by canceling and renegotiating trade agreements. But his efforts have backfired. The U.S. is simply too enmeshed with the world to win back jobs by simply pulling back from trade.

Trump based his tariffs on the assumption that the U.S. is so powerful that it could unilaterally impose tariffs on trading partners without them retaliating.

Related: U.S. tariffs on China are illegal, says World Trade Organization

As Peter Navarro, director of the White House National Trade Council, said in 2018: “I don’t believe any country is going to retaliate for the simple reason that we are the most lucrative and biggest market in the world.”

But this prediction has not come true. In fact, the opposite has happened: Our trading partners have promised to retaliate “dollar for dollar,” in the words of Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s deputy prime minister.

When Trump lashed out at Chinese and Canadian suppliers of metals and metal-using goods, they predictably retaliated and the U.S. economy suffered for it. His tariffs on aluminum hurt U.S. industries that use aluminum, which are far more numerous than those that produce it.

And Canada answered Trump’s tariffs with countermeasures of its own, raising the price of U.S. aluminum and aluminum-containing goods—including washing machines made at the very Ohio plant where Trump first announced the tariffs.

Trump’s trade war with China has had equally dismal results. After Trump initiated this conflict by levying tariffs on Chinese-made goods, China retaliated with tariffs on U.S. agricultural goods.

American farmers have lost an important market—in some cases their most important market—and American taxpayers have borne the cost, as Trump has had to replace farm income with billions in compensation checks from the government.

In 2016, China bought $13.7 billion in U.S. soybeans. By 2018, that figure had fallen by nearly half, to $7.1 billion. Trump’s “tariff on Chinese products and the resulting retaliation by China on soybeans,” warned the Ohio Soybean Association, makes us less competitive in the global market” and virtually guarantees “negative effects on soybean prices and farmers’ incomes.”

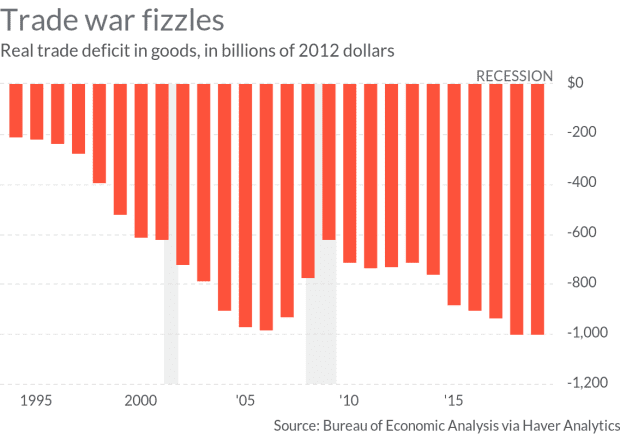

The U.S. trade deficit in goods has worsened under President Donald Trump.

Through all of this, Trump has pointed to the trade balance as his main barometer for how our industries are performing. Unsurprisingly, the trade balance has only gotten worse under his tenure—even before the pandemic hit.

Nor has his approach stopped offshoring by U.S. companies. In fact, investment in China by U.S. companies was higher in 2019 than in 2016, the year Trump was elected. This investment was led by manufacturing companies like General Electric GE, -1.57% and Tesla TSLA, -5.59%, who built new factories in China rather than in the U.S.

Election coverage: Here’s how key swing states are leaning in the presidential race — and how they’re weathering the recession

America must do better by its workers.

The last several years have shown that picking fights with trading partners around the world is not a winning strategy. To improve working people’s standard of living—at home and abroad—the U.S. needs to work with its trading partners, not against them.

Three ideas to start moving in the right direction include:

Rein in footloose capital. Trump’s tariffs haven’t stopped offshoring, but the problem can be addressed by eliminating treaty rules that prohibit capital controls, which limit corporations’ ability to relocate operations to push down wages. The damage done by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which slashed corporate taxes on foreign profits from 28% to 10% and incentivized U.S. companies to offshore production, should also be reversed.

Don’t let trading partners undercut U.S. workers on the backs of their own workers. Congressional Democrats’ changes to the United States—Mexico—Canada Agreement (USMCA)—the new NAFTA—helped place a floor under Mexican wages. These reforms should be strengthened and incorporated into all future agreements.

Reform trade advisory panels. The U.S. Trade Representative’s “advisory committees” should represent workers, small-business owners, and public interest groups to ensure the committees function as intended.

As the 2020 presidential campaign comes to a head, voters will be reckoning with Trump’s record. On trade, it’s time to accept that Trump’s approach hasn’t worked, and Rust Belt workers are paying the price.

Rebecca Ray is a senior academic researcher at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center. She holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Massachusetts—Amherst. She’s a co-author of the report “How U.S. Trade Policy Failed Workers—And How to Fix It,” released by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, the Institute for Policy Studies, and Groundwork Collective.

More from MarketWatch:

Yes, the U.S. economy really does need more fiscal stimulus—and the stock market knows it

Here’s where Trump and Biden stand on China and other trade issues

Biden talks up his plans to boost U.S. manufacturing as he visits Michigan