This post was originally published on this site

Niall Carson/Zuma Press

In recent weeks, the U.S. Treasurys market has shown signs of indigestion as the federal government auctions off record amounts of debt which may be starting to overwhelm investor appetite.

While investors globally appreciate the higher yields on U.S. debt compared with negative rates in Europe, new issuance may soon swamp the Federal Reserve’s asset purchases in the coming months if the central bank does not step up its pace of bond-buying.

Even so, investors don’t see Treasury prices buckling under the weight of new supply, with few predicting the 10-year Treasury yield returning to its pre-pandemic levels.

“We’re seeing some weakness with regularity on auction weeks,” said Tom Graff, head of fixed income at Brown Advisory, told MarketWatch. “Sometimes when there’s a large amount of supply to digest. There’s a little bit of a bump.”

The 10-year Treasury note yield TMUBMUSD10Y, 0.745% moved up to 0.75%, around the top of its two-month trading range on Thursday, following the Federal Reserve’s decision to aim for an “average inflation” target of 2%.

Though this week’s round of shorter-dated debt auctions have fared well, reflecting the Fed’s commitment to keeping interest rates low for an extended time, investors and other market participants have struggled to take down the auctions for longer maturities.

But Graff says some of the poorer sales were more of a reflection of the lack of capacity from banks and other broker-dealers to temporarily take the new supply onto their balance sheets, and that yields were sometimes trading prior to the auction at lower levels where demand fell short of supply.

Much of the confidence that long-term yields will remain low comes from the Fed’s strong commitment to keeping monetary policy easy and financial conditions loose as part of its efforts to support the U.S. economi recovery from the coronavirus pandemic.

In the minutes of its most recent policy meeting, the Fed central bank was unwilling to adopt a policy of yield-curve control, that is, targeting yields for certain maturities through bond purchases. Yet the potential for it to be brought out of the Fed’s toolkit has been enough to frighten away traders that might look to sell long-dated Treasurys to profit from higher yields.

“It’s impossible for the Fed to allow rates to yields rise too much,” said Bastien Drut, a senior strategist at CPR Asset Management, in an interview.

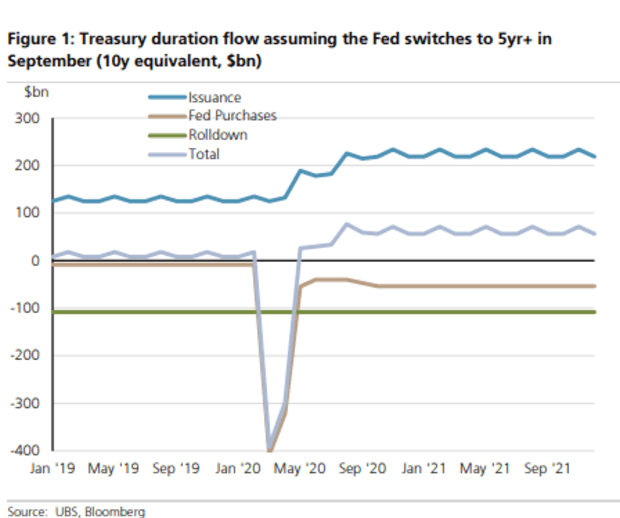

Still, Tom Cloherty, chief rates strategist at UBS, says the increased issuance by the U.S. Treasury on the long-end of the yield curve may be canceling out the Fed’s purchases, half of which are focused on maturities of less than five years.

That has led to calls for the Fed to shift the focus of its $80 billion of monthly asset purchases to bonds with extended maturities at the Fed’s September’s meeting.

But even after making such a tweak, the increase in issuance will still exceed the central bank’s purchases at their current pace, as the chart from UBS below shows.

“The equilibrium between the Fed purchases and the net issuance of Treasurys will be completely unbalanced,” said Drut.

Even so, investors aren’t panicking at the prospects of a supply-induced selloff as it isn’t expected to translate into a substantial increase in bond yields.

With COVID-19 holding down the U.S. economic recovery and inflationary pressures, the impetus for higher rates remains weak.

“On the margins, the inflation and growth story isn’t wildly changed for bond yields to go way, way higher,” said Graff.