This post was originally published on this site

A view of Lower Manhattan.

AFP/Getty Images

The middle of New York City remains a ghost town almost six months after the pandemic led throngs of office workers to flee its packed city streets.

But dead forever? Not a chance.

“Absolutely, positively, not,” said Bill Rudin, a New York City real estate scion and chief executive of Rudin Management Co., which owns a sprawling portfolio of office towers, luxury apartments and recently the ground-up Dock 72 workspace at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

“It’s not dead. It’s very much alive.”

Rudin pointed to the burst of office-leasing deals in July, roughly 2.3 million square feet in all, a month after real-estate agents were allowed to resume in-person property tours under “Phase 2” of the city’s reopening plan.

Then came Facebook Inc. FB, +8.22% in August, inking a splashy 730,000-square-feet office lease with Vornado Realty Trust VNO, -3.66% at the landmark Farley Building, a former Manhattan post office that’s part of a $2 billion redevelopment near Madison Square Garden. Terms weren’t disclosed, but the move-in date was pegged as 2021.

Even as the pandemic bore down on the city, Amazon AMZN, +2.85% bought the former Lord & Taylor building on Fifth Avenue from struggling co-working startup WeWork, reportedly paying $1.15 billion. Amazon plans to occupy the property in 2023, and hire 2,000 white-collar workers in New York, the New York Times reported earlier this month.

The spate of deals arrived as a breath of fresh air for Manhattan landlords, who saw office-leasing activity plunge to a 25-year low in the second quarter as the city became the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tenants signed up for a mere 2.5 million square feet of office space from April to the end of June, down from an average 8.4 million square feet per quarter over the past three years, according to Cushman & Wakefield CWK, -0.68%, a real-estate brokerage.

That played into a key fear for property owners, that companies forced into a shotgun wedding with remote work might opt to never return to the office, or decamp to lower-cost cities and suburbs.

“Businesses have realized that they don’t need their employees at the office,” James Altucher, a comedy club owner, former hedge-fund manager and prior MarketWatch columnist wrote in his viral essay claiming New York City is “dead” forever.

“They say that after every crisis,” said Marty Burger, chief executive at Silverstein Properties, another family-held New York City property giant, whose office skyscrapers include 3, 4 and 7 World Trade Center.

“We’ve proven them wrong each time.”

Burger says working from home serves as a “short-term solution, not a long-term solution” for many industries, pointing to limitations of Zoom ZM, +1.66% calls and other videoconference platforms for conducting business.

Imagine a consumer-goods team virtually pitching “a new lipstick” to colleagues, he said, or mentoring a young associate on how to rise through the ranks from home.

After Labor Day, a new look

New York City waged a nearly 100-day battle to contain the coronavirus after its first confirmed case in March. But the next big test for the city will come after Labor Day, when many companies expect to recall more staff to Manhattan offices.

That’s also when school buildings are set to reopen, although with a third of students recently electing to attend online and with the city encouraging the use of schoolyards, nearby parks and other open spaces for classes, according to The City.

New York Fashion Week also got a green light to proceed in September through a mix of live and virtual events, although with face masks, temperature checks and no spectators for indoor shows.

Such precautions look to be the new “normal” for a while.

Manhattan Borough President Gail Brewer told MarketWatch that many of the real-estate owners she talks with have a plan for three years from now, in terms of seizing on a recovery, even though many tenants have immediate concerns.

Since last week, Brewer’s been hitting the streets and hearing about small-business woes, while she’s parceled out face masks and hand sanitizer to small-business owners, from bodegas to Chinese takeouts.

To her own surprise, “the hardest-hit stores have been the shops selling tchotchkes to tourists,” Brewer said, referring the trinkets, T-shirts and other memorabilia popular with visitors. One shopkeeper told her about making only $3 in sales over a recent day, while owing some $100,000 in unpaid rent.

Brewer pointed to landlords willing to cut tenants slack on back rent, but also the city’s deep fiscal troubles, the worst since 1970. “Subways and schools bring people to New York City,” she said, noting their role in fostering the next generation of New Yorkers. “I worry about those two.”

JP Morgan Chase’s JPM, -1.40% Daniel Pinto told CNBC this week that some degree of working-from-home is here to stay, a change he thinks could reduce stress on public transportation and result in a smaller real-estate footprint.

Read: Here’s a snapshot of what Wall Street’s coronavirus protocols look like for returning to work

Still, Burger at Silverstein Properties expects the pandemic’s impact on office properties to be neutral, once the dust settles and companies sort out their game plans.

“Some firms will take more space. Some firms will learn to live with less space,” he told MarketWatch, adding that his employees will be recalled to the office after Labor Day.

“We think it’s important to bring them back.”

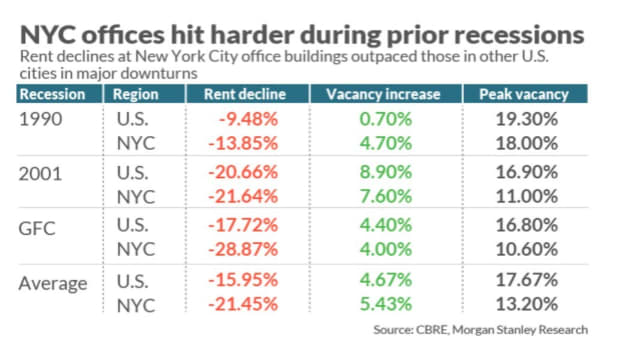

Morgan Stanley office-property analysts have a less optimistic outlook. They expect New York City office vacancies to peak above 11% over the next six to 12 months, eclipsing the 10.6% high-water mark following the global financial crisis.

Critically, they also foresee office rents declining 15% over the next 12 months, although that’s less dire than their initial 20%-25% forecast in May, as landlords struggled to collect rents.

Here’s how past recessions impacted New York City office space.

Meanwhile, Gov. Andrew Cuomo recently extended an eviction moratorium to protect commercial-property tenants until Sept. 20.

“There are a lot of developers who are very hungry to find distressed real estate,” said Robert Rynarzewski, head of commercial real estate at Piermont Bank in Manhattan, which lends to high-net worth clients owning two to 15 properties, not $1-billion skyscrapers.

“New York City, to me, is ever changing and ever evolving. It’s never dying,” he said, even though the lines for a morning coffee in midtown are gone and his clients want to buy suburban offices.

“It ebbs and flows.”

Until now, there hasn’t been a deluge of distressed real-estate deals, like the ones in 1990s that came after the collapse of the savings-and-loan industry, which led banks to dump real-estate loans in bulk onto the market.

Some hedge funds and private-equity lenders have been wrangling over trophy properties in the city, but mostly it has been a waiting game to see what comes next, after commercial real-estate transaction volumes plunged 69% in the second quarter from a year prior.

“Right now there’s a bit of paralysis,” said Scott Homa, head of Americas office research at Jones Lang LaSalle, a commercial real-estate company.

“It will likely continue to be that way until there’s a sense that the market has hit a floor and tenants can resume making long-term space decisions.”