This post was originally published on this site

In this photo provided by Jason Koski, Bryan Maley, right, a graduate student in the Master of Public Health program at Cornell University, interviews a student on campus about mask-wearing experiences as part of a public health survey, Friday, July 30, 2020, in Ithaca, N.Y. (Photo: Jason Koski/Cornell University via AP)

Christian Baran has been thinking about the value his college tuition is supposed to be buying since the spring.

Baran, 21, was a sophomore at Cornell University when the school, like most others, rushed students home and into online classrooms in March as the reality of the pandemic began to set in. Baran thought his family might get some sort of tuition refund, given that the experience was so different from what he thought his tuition was buying.

“But we didn’t get anything,” Baran said. Like almost every college in the country, Cornell didn’t give back any tuition money, but the school did provide rebates for housing and dining contracts.

Now, as the start of the fall semester at the school approaches, the school is moving forward with a planned tuition increase of 3.6% that was approved in January before the pandemic. Cornell, which is planning to bring students back to Ithaca and offer some in-person classes, is expecting to increase the amount of financial aid it awards, and will be drawing more than typical from its endowment in fiscal year 2021 to generate an additional $15 million.

Christian Baran decided to take a semester off from Cornell University in part because he didn’t feel it was worth the money.

Still, it’s not enough for Baran. “It seems ridiculous to keep paying the same amount for what seems to be an inferior hybridized education,” he said. And that’s a best-case scenario, assuming the school doesn’t end up shifting completely to remote instruction, as some have already done.

So instead of paying Cornell tuition, Baran decided to enroll in community college for the fall semester and hopefully return to Cornell in the spring. “I don’t think that it’s worth it,” he said.

Cornell is one of at least 42 U.S. institutions whose endowments are in the top 100, that is going ahead with a planned tuition increase for undergraduates this upcoming academic year, according to a MarketWatch analysis. We found that 35 others are planning to keep tuition the same as last year and five are decreasing tuition.

Tuition cuts are rare, but it’s also an extraordinary year

That some schools are cutting tuition represents an extraordinary break from colleges’ typical policies — college costs have skyrocketed 161% over the past 30 years and between the 2009 and 2010 academic year and the 2019 and 2020 academic year colleges increased tuition nearly 2% on average per year, according to the College Board.

But this is also an extraordinary year. A global pandemic and accompanying economic downturn has made it more difficult for many families to afford college. At the same time, the pandemic has changed what families are paying for. Under the best of circumstances, students will return to campuses devoid of many of the usual college activities — spontaneous meetings in the student union, robust club events, and yes, parties.

And if the experiences of schools that have already brought students back is any indication, those plans are likely to go awry, forcing students into even more restricted environments or sending them home.

These dynamics stretched colleges’ business models, which had been showing signs of weakness for years. “Generally speaking, the pandemic is not going to create a significant shift in the price of tuition,” said Dominique Baker, an assistant professor of education policy at Southern Methodist University.

That’s because colleges lost housing, dining and other revenue when they sent students home this spring and, in addition, they’ve had to spend more on technology, plexiglass and other adjustments to make a fall semester work, Baker said. Schools will also lose funds if enough students decide to take a gap year and enrollment dips significantly.

“The only ways to try to make this up are to hold on to revenue streams you already have because if you don’t do that this leads to massive furloughs and layoffs, among other cost cutting measures,” she said.

Colleges begin thinking about tuition policy months in advance

Colleges usually begin thinking about their tuition strategy in the fall of the previous academic year, said Jim Hundrieser, the vice president for consulting and business development, at the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

They typically start by thinking about what increased costs they will have and whether those will be one-time costs or fixed costs, he said. Colleges have looked for ways to cut some of their typical costs this year, including furloughing employees, freezing pay and limiting retirement contributions, but many of their largest fixed costs, like faculty salaries and health care remain large and possibly growing.

Schools will also look to see whether they expect sources of revenue other than tuition to be able to cover some of these costs, Hundrieser said. Philanthropy, one of the typical sources of revenue for schools, is likely to be down this year if previous downturns are any indication.

Colleges will also turn to their endowment to cover expenses, typically drawing around 4% per year from the fund, Hundrieser said. But it can be difficult to tap the endowment for more than officials initially planned because the funds are often restricted and because the idea behind the endowment is to make sure the university runs in perpetuity, Hundrieser said.

“Endowments aren’t just one pot of money, they’re a bunch of small pots of money,” said Robert Kelchen, an associate professor of higher education at Seton Hall University. “Colleges don’t like spending large amounts of money out of an endowment in any given year,” Kelchen said. “On the other hand, the endowment is also there for a rainy day and it’s pouring right now.”

Perhaps one of the biggest factors driving a college’s tuition policy is how much money they’re going to give away, Hundrieser said. At private schools in particular, most families don’t pay a college’s advertised or “sticker” price.

Instead, they get a discount. The average discount rate — or the amount of grant aid colleges offer as a percentage of their tuition and fee revenue — for the 2019-2020 academic year was 47.6% according to NACUBO.

Families don’t learn what kind of discount they’ll receive until a student applies, gets accepted and receives a financial-aid package from their school. Often, colleges award these scholarships based on financial need, but in some cases, colleges use what’s called merit aid — or scholarships for good grades or other characteristics — to lure families who can afford to pay the full, or near full sticker price and will be persuaded to sign the check if they believe they’re getting a deal.

“ ‘This is the question many, many chief finance officers are asking and really beginning to evaluate — if we’re just going to raise [tuition] and give it all away what’s the point?’ ”

This high-tuition, high-aid strategy started to ramp up in the wake of the Great Recession and some institutions are growing more skeptical of it, Hundrieser said. “This is the question many, many chief finance officers are asking and really beginning to evaluate — if we’re just going to raise [tuition] and give it all away what’s the point?” he said.

The strategy also puts strain on families, particularly low-income families who see a college’s high five-figure sticker price and immediately dismiss it as a possibility, said Mark Huelsman, associate director of policy and research at Demos, a progressive think tank.

In addition, many of the schools with the most generous financial-aid packages for low-income students, don’t educate a large share of the low-income student population, he said. Even as most colleges have increased their financial-aid budgets during the pandemic, the messaging of the sticker price is still important, he said.

“ ‘Imagine any financial transaction you make and someone says the price of this thing is $100,000, but you are very likely to pay nothing, but first you have to fill out all these forms.’ ”

“Imagine any financial transaction you make and someone says the price of this thing is $100,000, but you are very likely to pay nothing, but first you have to fill out all these forms,” Huelsman said.

The focus on discounting can also make it difficult for colleges to reverse course once they’ve made a tuition decision, Hundrieser said, because they’ve already awarded the aid they’re going to give out and tweaking tuition will affect the amount of revenue they bring in. Still, some schools have been able to make changes in light of the pandemic.

Some schools have been able to offer tuition cuts

At Hampton University, a Historically Black College in Hampton, Va., the school’s president, William Harvey, announced in early July that the school would offer only remote instruction in the fall and a 15% discount on tuition and fees.

“This is going to be a financial burden for us, but it’s also a financial burden for parents and others,” Harvey said he remembers thinking as he weighed and investigated the idea of a tuition cut with other university officials.

Ultimately, he decided to go through with it and one of the reasons Hampton was able to do so is because the school is “pretty financially sound,” Harvey said. Though not in the top 100, the school’s endowment has grown over the past several decades and is now worth more than $250 million. Resources like an enrollment stabilization fund and a real-estate foundation, help too, he said.

In addition, after the school made the decision to cut tuition, they received a “god-given gift,” from MacKenzie Scott, Jeff Bezos’ ex-wife, of $30 million, Harvey said. Those funds can be used at the discretion of the president, he said, and the school plans to use part of the money to help mitigate the financial impact of the tuition cut.

Daniel Kim, a senior at Duke University, started an online petition last month asking his school to decrease tuition after he saw that at some other schools where petitions circulated, officials cut the sticker price. In early August, Duke announced that, instead of increasing tuition 3.9% as originally planned, it would freeze tuition at $55,880 and adjust certain fees based on where students plan to live this fall.

“ ‘It’s the same tuition that we’re paying as last year, except last year we had in person classes, extracurriculars, the whole social experience.’ ”

“It’s the same tuition that we’re paying as last year, except last year we had in -person classes, extracurriculars, the whole social experience,” Kim said, though he appreciates that they didn’t go forward with the increase.

Duke invited freshmen and sophomores back to on campus housing this fall and is hoping to bring juniors and seniors back in the spring, according to Erin Kramer, a Duke spokesperson. The school is offering a mix of in-person, remote and hybrid classes. Right now, Kim is planning on taking his classes from his childhood home in Northern Virginia.

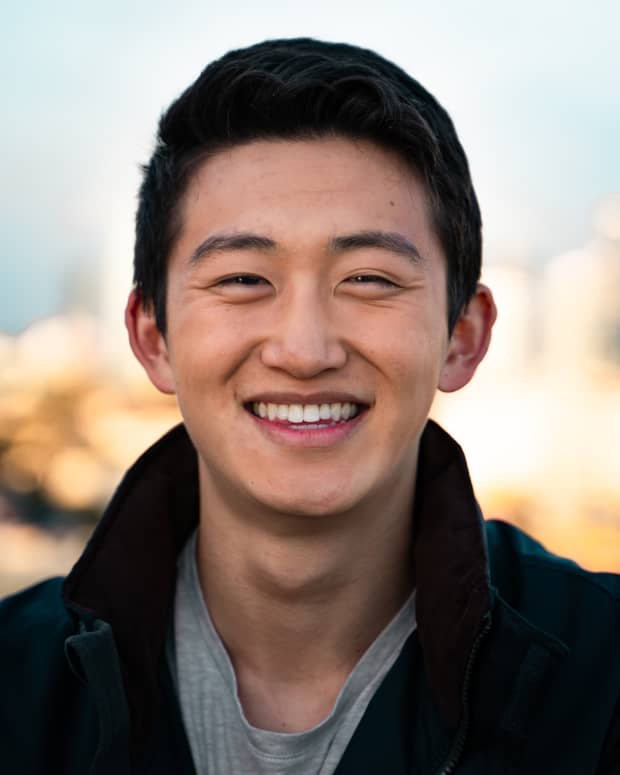

Daniel Kim started a Change.org petition asking for his school, Duke University, to reduce tuition.

Kim, who is majoring in theater and minoring in biology and cinematic arts, wasn’t pleased with his remote courses in the spring. “I kept pounding my head against the floor, group chats were popping during it.” he said. But at least so far, his classes this semester have been satisfactory. “I’m hoping just to grind it out.”

Annisa Salsabila, a sophomore at the University of Texas, is skeptical she’ll get the value she’s paying for from her courses. The 19-year-old is a neuroscience major and won’t have access to the labs and research experiences she would under typical circumstances.

UT is offering some courses in person, but is also giving students the option to take all of their courses online, which Salsabila is electing to do because she believes it’s the safest option.

At UT, tuition will be 2.6% higher this fall than last year, an increase approved in November 2019 by the University of Texas System Board of Regents. The uptick is based on the rate of inflation per the higher education price index, according to a spokeswoman, an inflation index that tracks the cost drivers of higher education.

“The cost of education is a major concern for students and families, more so now than ever,” J.B. Bird, a UT spokesperson, wrote in an email. “We have focused our fall planning efforts to deliver an exceptional educational experience while also maintaining the health and safety of the UT community.”

Annisa Salsabila worries about how a tuition increase at her college will impact her long-term.

Still, to Salsabila the increase feels “ridiculous.” She expects to borrow more in student loans to cover the uptick. “It just places more financial burden on me and my family in the long run,” she said.

Public colleges don’t have complete control over their tuition policies

Like many public colleges, UT is governed by a board of regents, whose members are appointed by the governor. At some public colleges, the governing board is actually elected by the state’s voters. Either way, state leadership does play a role in how public colleges set their tuition, though there’s often a back and forth between the school and legislatures.

If the last recession is any indication, public colleges will likely face cuts in the funding they receive from the state lawmakers, a factor which could push them to look for money from other sources — like students’ and families’ pockets. At the same time, these schools may face pressure from state legislatures to keep tuition low.

That dynamic could exacerbate inequities already present in our higher-education system. Public colleges, particularly regional state schools and community colleges, that are likely to face funding challenges over the next few years, are also those that serve the bulk of the country’s low-income and Black and Hispanic students, Huelsman said.

“At the same time you have institutions that not only can weather the storm because of their own resources — whether that’s an endowment, or a brand name or a demand for their services — that they feel like they don’t have to respond to the economic pain facing a lot of Americans,” he said, “the families and the students who are most impacted by the economic crisis were more likely to go to colleges that were also more impacted by this economic crisis.”

Though we’re unlikely to see broad cuts in tuition in the years following the pandemic, it’s possible that some, individual students could get a break, Kelchen said. Colleges were already bracing for demographic trends that mean there will be fewer 18-year-olds heading to college in the coming years and the pandemic will only exacerbate colleges’ hunger for students.

“If you can get students to pay that full price, there’s less of a reason for you to cut that listed price because you’re giving up revenue,” he said. “It’s easier for colleges to give discounts to those who ask.”