This post was originally published on this site

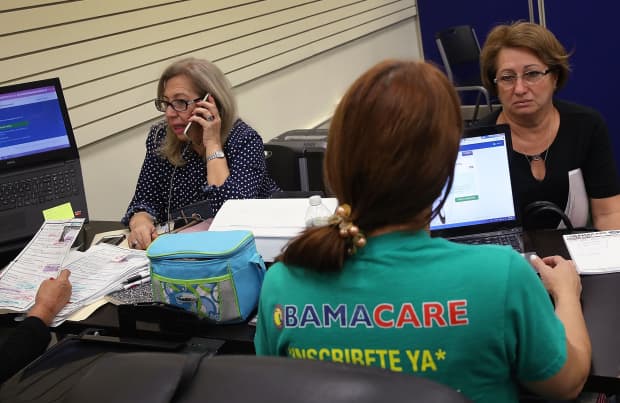

Two women speak with insurance agents as they shop for insurance under the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare.

Getty Images

Ten years after the passage of the Affordable Care Act, the Trump administration is now asking the Supreme Court to overturn it. Yet it’s now clear that the ACA has brought significant improvements to the lives of millions of Americans. Today, they enjoy more health-care coverage, with greater access, better outcomes and less cost.

One segment in particular gained the most: pre-Medicare adults from ages 50 to 64. Before the ACA, the number of uninsured in that group reached 8.9 million people. Insurance companies rejected more than one in five of their applications. Those who remained uninsured received fewer basic clinical services. They were more likely to experience health declines.

But after passage of the ACA, 5.6 million of them — 9% of the 62 million in the pre-Medicare group — purchased coverage in the individual health insurance market. As a result, their uninsured rate fell from over 14% in 2013 to less than 9% in 2018.

Now the new question: Have there been improvements in the health status for the pre-Medicare population? If so, they would likely be somewhat more resilient to COVID-19. So both of us began to analyze data from the Health and Retirement Study, and tracked changes in the group’s well-being. We chose the years 2010 and 2016.

Data shows health improvements

What we found was good news. On balance, middle-aged Americans are better off now than before passage of the ACA. Key health metrics improved. Reported levels of depression are down. Smoking has declined. Those who say their health improved over the prior two years rose from 12% to 16%. The number who say their health had deteriorated has diminished.

What’s more, their use of hospitals and nursing homes over the period has lessened. Given the high pandemic-related mortality rate among residents of nursing homes, this is a particularly critical finding.

To put it into perspective: the two-year incidence rate for the group’s nursing home admission in the pre-ACA (1.7%) and post-ACA (0.7%) period is a drop of 59%. Annually, that translates to 284,000 fewer admissions.

And far fewer deaths: Some estimates suggest that ultimately, upwards of 20% of nursing home residents may die from COVID-19.

So assume that roughly 15% of new admissions from this population are particularly frail and vulnerable and end up as residents with greater than two-year stays. This annual reduction in admissions would mean up to roughly 8,500 fewer deaths per year.

We also found that out-of-pocket medical costs for them was reduced by 11%, even though medical inflation increased by more than 25% during the period. Fewer of them retired involuntarily – noteworthy, because declining health is a primary reason those between ages 50 and 64 leave the workforce. And fewer were living below the federal poverty line.

Lower risk, better outcomes

So what does this mean in the context of COVID-19?

The pre-Medicare group is now at somewhat lower risk of a severe outcome due to the pandemic. With less use of hospitals and nursing homes, and more staying at home, they have reduced their risk.

With greater access to insurance, and lower out-of-pocket expenses, they are less likely to put off early treatment; cost is no longer a significant barrier. And because employment is no longer tied directly to health coverage, they may feel less pressure to work when they are ill.

Social isolation can be problematic for those middle-aged and older, who often are lacking social support resources. The decreased rates of depression among the group is likely due to greater access to mental-health services. Clearly, this helps mitigate the negative effects of the stay-at-home orders and the anxiety of a pandemic.

Our findings suggest a continued need not only to safeguard the ACA but to strengthen it — and keep millions of vulnerable Americans safe and healthy. The Trump administration’s move to overturn the ACA, particularly during this extraordinary time, will only add to our current challenges.

Marc Cohen is a clinical professor of gerontology and co-director of the LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Jane Tavares is a research fellow at the LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston.