This post was originally published on this site

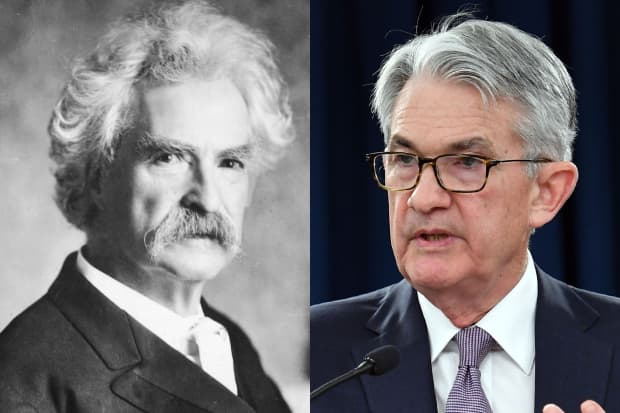

Mark Twain may have had a lesson for Jerome Powell.

Getty Images

When it comes to essential reading for a modern central banker, John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman have nothing on Mark Twain.

After all, Tom Sawyer convinced his friends to complete his punishment of whitewashing a fence by facetiously proclaiming how much fun he found the tedious task — even getting them to effectively pay for the privilege. While the Fed isn’t relying on the same chicanery and reverse psychology employed by Twain’s fictional hero, it has managed to get market participants, so far, to do some of its heavy lifting when it comes to backstopping the corporate credit market.

The Fed, which launched its Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility in March, had tapped only 4% of its $250 billion asset-buying capacity as of June 30, noted Peter Wilson, global fixed income analyst at Wells Fargo Investment Institute, in a Monday note. Investors, however, have rushed into the market to buy far more.

Wilson observed that as of June 30, the Fed facility had bought $9.6 billion in assets — almost $8 billion in corporate bond exchange-traded funds and around $1.6 billion in individual bonds. Meanwhile, the total assets of the largest U.S. investment-grade corporate ETF had doubled since March 19, hitting $56.5 billion as of July 14.

As a result, corporate bond spreads — the premium investors demand to hold the debt over “risk-free” U.S. Treasurys — have narrowed sharply despite the lack of more aggressive buying by the central bank, meaning that private demand “has done the Fed’s work, swamping those modest purchases,” Wilson said.

The literary comparisons only go so far. The Fed’s success is attributable, in part, to its credibility.

“If market participants have sufficient faith that the Fed will buy enough bonds to stabilize and narrow credit spreads, then they will likely seek to buy before those spreads are narrowed—and that is exactly what happened. A strong belief that the Fed ‘has the market’s back’ can be a powerful—and ‘cheap’—form of financial stability policy,” Wilson wrote.

That isn’t the only driver. Wilson also cites the “portfolio rebalance effect,” which academics have described as part of the mechanism of government bond purchases through quantitative easing.

The idea, Wilson noted, is that QE stimulates the economy by lowering returns on low-risk assets, in this case, Treasurys, to a level that effectively forces private-sector investors to rebalance their portfolios by buying more risky assets, such as corporate bonds.

And then there’s a third channel — cheaper currency hedging costs, Wilson said. By cutting the fed-funds rate to virtually zero, the differential between rates in the U.S. and the rest of the world has been significantly lowered. That makes it much cheaper for overseas buyers of U.S. dollar-denominated bonds to hedge their currency risk.

“This means that Japanese institutions (for example) can buy U.S. bonds, remove the risk of dollar depreciation undercutting returns, and in many cases, achieve a yen-based yield better than that seen for several years, and—importantly—far above the yield available on equivalent domestic (Japanese) assets ,” he wrote.

Meanwhile, the narrowing of corporate yield spreads relative to Treasurys, in turn, may be driving demand for stocks, analysts said.

Equities have roared back to reclaim much of the pandemic-influenced fall that took the S&P 500 SPX, +0.16% from a record close on Feb. 19 to a 34% fall through March 23. The large-cap benchmark ended around 4% below its all-time closing high on Monday, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, +0.59% remained around 9.7% below its Feb. 21 record finish. The Nasdaq Composite COMP, -0.80% on Monday posted a record close.

Jonathan Golub, chief U.S. equity strategist at Credit Suisse, argued that the tightening of corporate spreads has been a more important driver than recent moves in the Treasury market, where yields fell in step with stocks during February and March but have subsequently flatlined.

“While rising yields signal an improving economy, they also contribute to a higher cost of capital — a negative for stocks. By contrast, tighter credit spreads signal economic vibrancy and lower the cost of capital — a positive.,” he said, in a Monday note. “Contrary to conventional wisdom, the economic signal from Treasury yields and spreads is far more important than the shifting cost of capital.”