This post was originally published on this site

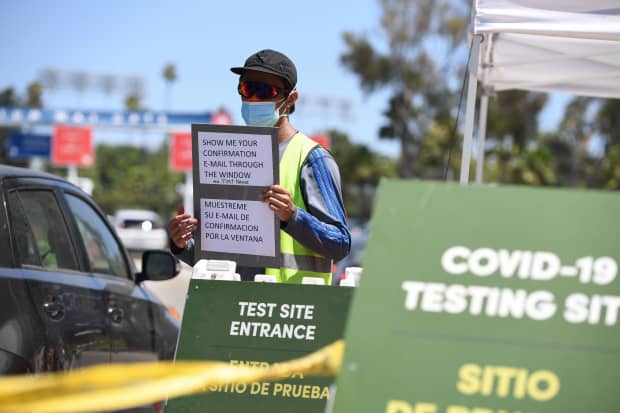

Staff at direct cars at a drive-through COVID-19 test site, July 15, 2020 at Dodgers Stadium in Los Angeles, California.

robyn beck/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

When people first started showing signs of coronavirus in the U.S. in March they were told they needed special permission to get tested.

If they didn’t fit into the high-priority bucket — which included health-care workers, people who were hospitalized, and people who recently traveled to China or came in contact with someone who did, they were often told to quarantine at home for 14 days.

At that time, there was an extremely limited supply of testing kits, which backfired by helping accelerate the spread of coronavirus across the country because so many cases went undiagnosed, said Ashish Jha, the director of the Harvard Global Health Institute.

Since then, “testing capacity has clearly gotten better. At that time it was completely awful and now it’s inadequate,” Jha said.

So far, the U.S. has performed more than 45 million tests total, averaging approximately 700,000 a day “and that’s continuing to go up week to week,” Admiral Brett Giroir, a member of the White House coronavirus task force, who oversees testing, told reporters on Thursday.

Turnaround times for commercial test results “continues to be an issue,” Giroir, the assistant secretary for health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, said.

Wait times of more than ten days have become the norm for many Americans. There are, however, stories of people who have had to wait 26 days to get their results.

“Once you get the lag of seven to ten days, it’s only marginally better than not doing the testing,” Jha said.

Approximately half of the tests being performed daily are conducted by commercial labs such as Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp, Giroir said. The rest are done “at point of care, which is a 15-minute turnaround, or in local hospitals, which is generally within 24 hours.”

“Only one state has an average turnaround time of greater than five days. Five states are between four and five days. 26 states are still three days or less, and the rest are between three and four days.” Turnaround times of 10 to 12 days represent outliers, he added. Still, CityMD Urgent Care locations in New York, for example, says patients must wait seven days minimum for their test result.

“ ‘Once you get the lag of seven to ten days, it’s only marginally better than not doing the testing’ ”

To reduce some state turnaround times, Giroir said he wants to transition to “care testing.” He also advocated for “pooling five samples into one.”

Doing so, health experts say, would help labs churn through negative test results. The downside is that it prompts an additional round of testing if coronavirus is detected in the pooled sample.

“It can decrease the turnaround time tremendously,” he said. However, Giroir said “the science is still being validated [and] the regulatory is still being authorized.”

The state of commercial testing in the U.S.

Quest Diagnostics Inc. DGX, +1.17%, one of the largest labs in the U.S. performing coronavirus tests, said that the average turnaround time for non-priority patients is “seven or more days” and “slightly more than one day” for priority patients.

“ “We will not be in a position to reduce our turnaround times as long as cases of COVID-19 continue to increase dramatically across much of the United States.’ ”

That’s after the company doubled its testing capacity compared to eight weeks ago, Quest said in a statement made on Monday. Testing capacity currently hovers at 125,000 tests a day, but by the end of the month, Quest said it expects to have the capacity to perform 150,000 tests a day.

“We will not be in a position to reduce our turnaround times as long as cases of COVID-19 continue to increase dramatically across much of the United States,” the company said. “This is not just a Quest issue. The surge in COVID-19 cases affects the laboratory industry as a whole.”

LabCorp’s LH, +0.90% experience is nearly identical to that of Quest.

Both companies say that recent demand for testing in light of the country’s record daily cases that continue to climb cannot be met under their existing constraints.

LabCorp said it has performed 7 million total tests since its test became available in March. Now it has been “able to process approximately 140,000 tests per day with plans to increase that to 150,000 tests per day this month,” a LabCorp spokesman said in a statement to MarketWatch.

Until recently, LabCorp said it’s been able to deliver test results back to patients on average between 1 to 2 days. “But with significant increases in testing demand and constraints in the availability of supplies and equipment, the average time to deliver results may now be 4 to 6 days,” he added.

“For hospitalized patients, the average time for results is faster,” LabCorp said.

But beyond the increased demand for testing, Jha pointed out that the long turnaround times cannot simply be pinned to one factor and can vary significantly at labs across the country.

For some, it boils down to not having enough reagents or swabs to perform the tests. For others, there could be a shortage of trained personnel to perform the tests that’s causing the delays.

But it was “completely predictable,” he said. “The system was not designed to do this level of testing.”

“We designed a horse and buggy to race in the Indy 500 and we’re having a hard time keeping up,” Jha told MarketWatch, and it’s “making it so much harder to control the disease.”

Not all labs across the country are being properly utilized

“There’s a lot of capacity to do tests that’s sitting on the sidelines,” Jha said. There are many labs in the U.S. that have the ability to do coronavirus testing, but aren’t “because they’re using the machines for something else.”

“They don’t know that, if they stop doing the other stuff, if they’ll be able to get paid to switch to coronavirus testing,” he added.

Companies with the technology would still have to repurpose their machines for coronavirus testing, Jha said. “They couldn’t possibly justify spending tens of millions of dollars if they don’t know that this is going to be financially viable.”

“ ‘There’s a lot of capacity to do tests that’s sitting on the sidelines’ ”

Giroir said that the price point the federal government pays to labs and suppliers of inputs for tests “is very fair and highly incentivizes people to do these tests.”

To ease their financial concerns, Jha recommended that the federal government pay them a portion of their fees upfront. He has spoken directly to some of those labs that are already in a financial limbo due to a decline in testing volumes because non-emergency health visits have fallen.

There are only a couple of companies that make the reagents to perform the tests

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has not publicly disclosed how many companies commercially manufacture reagents, but Jha believes there’s only a handful of companies doing so.

In March, President Trump invoked the Defense Production Act calling upon traditional car manufacturers like General Electric GE, -1.26% and Ford F, +1.78% to make ventilators. In April, he called upon 3M MMM, +0.73% to manufacture more N95 masks.

Jha said that could have been prevented if Trump invoked that same act to mandate “companies that don’t make the reagents for these tests to start making the reagents.”

“Those companies are working full time, but they can’t ramp up production any more than what they’ve done,” he said.