This post was originally published on this site

https://i-invdn-com.akamaized.net/content/pica83995e76970519b4a2bcc80d02e125a.png

(Bloomberg Opinion) — “Worrisome.” “Dangerous and aggressive.” “Abuse of documentation.” “Peak greed.”

These are just a few of the ways investors and analysts have described the riskiest corners of the debt markets in the past few days. From the U.S. to Europe, whether in collateralized loan obligations or junk bonds, the feeling that the reach for yield in fixed income is fast approaching a breaking point is becoming too powerful to ignore. It’s perhaps best encapsulated by a quote in the Wall Street Journal from Luca Cazzulani, a senior fixed-income strategist at UniCredit: “Investors are not really interested in safety, they are quite keen on yield.’’

That’s good, I guess. Because for those who still favor strong credit protection, it’s getting harder and harder to find it.

Let’s start with CLOs. Bloomberg News’s Adam Tempkin had an in-depth article this week with the headline “CLOs Are Packed With New Loopholes, Triggering Investor Backlash.” He reported that investors, analysts and credit raters are taken aback by managers’ efforts to “swap troubled loans, circumvent credit-quality limitations, and double down on risky wagers, largely in an effort to ensure they can pass crucial compliance tests, even if a large swath of a CLO’s underlying loans lose value.” Many understand that having a bit of flexibility in an illiquid market is a good thing when prices fluctuate but argue that provisions like these create the potential for severe losses if the credit cycle truly turns.

The same problem plagues the market for speculative-grade corporate bonds. Covenant Review, an independent research firm that analyzes debt documents for investors, published its 2019 year-in-review for the U.S. high-yield market this week and found many cases in which companies “ended up keeping some of the most dangerous and aggressive covenant provisions for bondholders.” A common strategy was for issuers to propose so many offensive covenants that even after a “hack and slash treatment to appease concerned bond investors,” they still got away with far more questionable terms than in the past.

It would be one thing if bond investors were compensated for those risks — giving up some safety for yield is a classic trade-off. But, of course, that’s not the case.

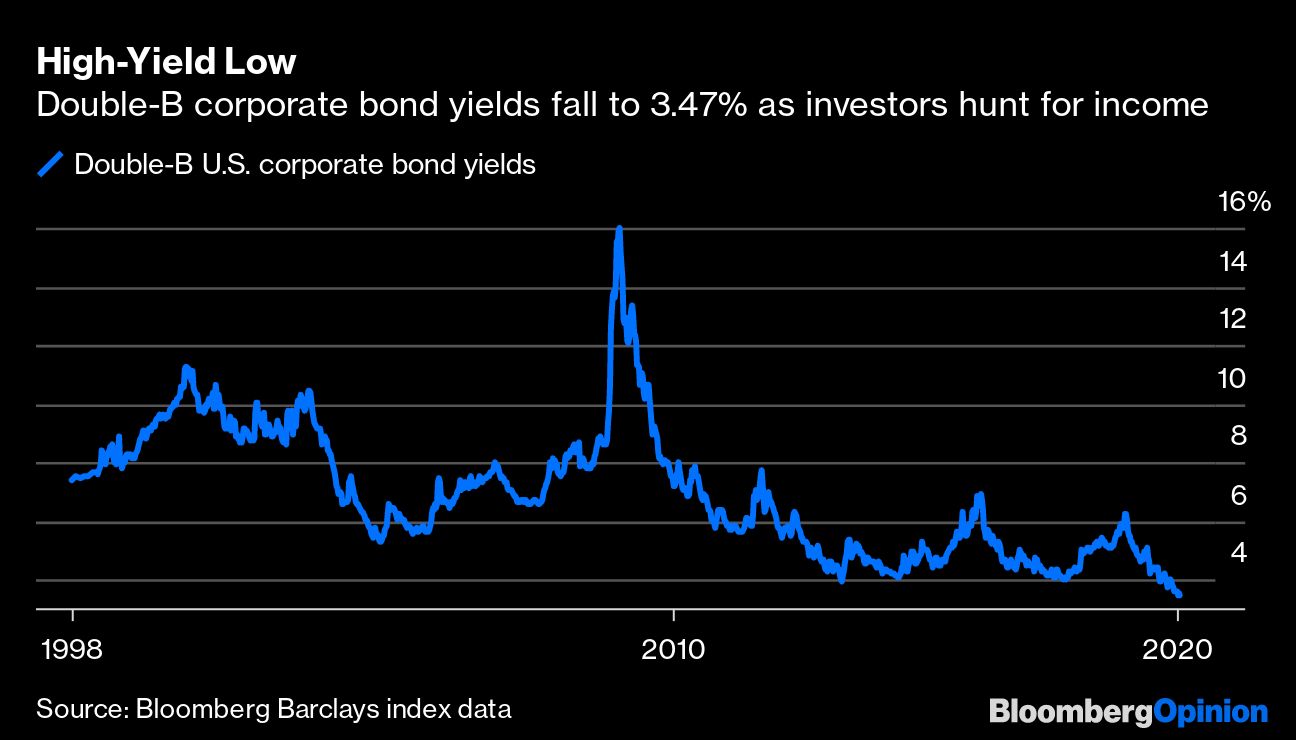

Rather, the yield on an index of double-B U.S. corporate bonds hit a record low of 3.47% this week. VICI Properties, a double-B rated real estate company that develops entertainment and hospitality centers, priced $750 million of five-year bonds with a 3.5% coupon, the lowest for that maturity in more than six years. To be clear, it’s not any better elsewhere up the credit spectrum, as yields on a Moody’s Corp. index of triple-B corporate bonds and a Bond Buyer index of municipal debt are both around the lowest since 1956. Even triple-C yields have fallen by 200 basis points in two months.

Record-setting interest rates aren’t limited to America. In Austria, as my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Marcus Ashworth wrote, Erste Group Bank AG priced a so-called CoCo bond to yield 3.375%, the second-lowest coupon ever for the risky debt. And European high-yield bond sales are poised to top $11 billion this month, the most-ever for January.

By now, it’s possible that the $100 trillion global bond market has simply become immune to reaching unprecedented levels. But the potential for complacency is scary, especially when someone like Bob Prince, who helps oversee the world’s biggest hedge fund at Bridgewater Associates, declares that the days of a boom-and-bust economic cycle are over.

This brings to mind a piece of investing advice that has always stuck with me: Bull markets don’t end when everyone is on high alert for what could go wrong. It’s when everyone willfully chooses to ignore those warning signs that the cycle inevitably turns.

The combination of weak credit protections and historically low yields on the riskiest corporate debt should be a clear red flag. Instead, when asked about financial-market bubbles, the one thing that came to mind for JPMorgan Chase (NYSE:) & Co. Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon was negative-yielding sovereign obligations. “Do you know anyone who’s actually bought a negative interest rate bond?” he asked CNBC’s Andrew Ross Sorkin. “I would never buy a negative rate bond. Not unless I was forced.”(1)

I get it. It’s tempting to bash negative-yielding bonds and anyone who owns them. Even though it has been several years since sovereign-debt yields fell below zero in Japan and some European countries, the concept still boggles the minds of Wall Street veterans. Who would purchase a security that locks in a loss if held to maturity?

But I would pose the same question to buyers of speculative-grade securities at these rock-bottom yields. If you’re still of the mind that economic cycles exist, then it stands to reason that the longest expansion in U.S. history is long in the tooth. Will a sub-3.5% yield on double-B bonds, or sub-5% on single-B bonds, be enough to cancel out principal haircuts in the case of default? Perhaps. But it’s worth remembering that lending to the wrong companies can also lead to losses — and possibly large ones — even if dicey companies have largely avoided disaster in recent years.

Now, there are some nascent signs that investors are anxious about their ability to pick winners after years of just about every wager paying off. Bloomberg News’s Caleb Mutua this week highlighted research from Barclays (LON:) Plc that showed junk bonds experienced a much sharper sell-off when downgraded in 2019 than in previous years. Usually, bond traders pride themselves on having superior information and being ahead of the credit raters. That confidence might be wavering.

Whether those fleeting jitters turn into anything more remains to be seen. Certainly, the Federal Reserve and other central banks aren’t about to do anything to derail the economic expansion with inflation still in check. And as long as yields and spreads remain near these lows, investors probably won’t lose much sleep over the daunting record $1.2 trillion of U.S. speculative-grade debt that’s set to mature through 2024.

Yet just because there’s no clear catalyst for a reversal today doesn’t mean investors are safe from a nightmare scenario in the future. At the very least, they should push for stronger protections when they buy new bonds or loans. As it stands, if and when the credit cycle turns and the losses mount, they’ll have no one to blame but themselves.

(1) Bloomberg News’s Liz Capo McCormick (NYSE:) quickly pointed out that plenty of Americans own negative-yielding debt, through Vanguard’s Total International Bond Index Fund.